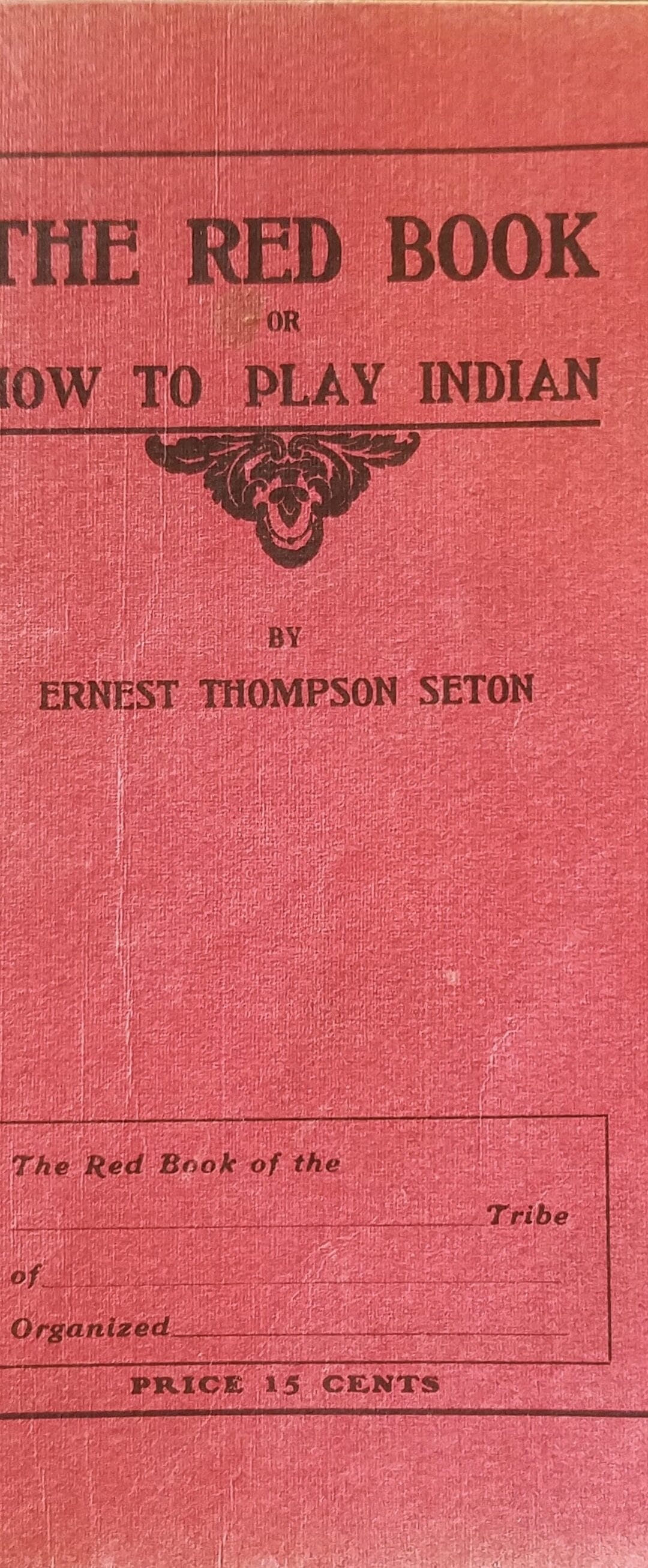

The Red Book or How To Play Indian by Ernest Thompson Seton

In 1903 Ernest Thompson Seton published a pamphlet through the Curtis Publishing Company titled “How to Play Indian. Directions for Organizing a Tribe of Boy Indians and Making their Teepees in the True Indian Style.” This became a foundational document for the Scouting and Woodcraft movements. It was first known as “The Red Book” (until a magazine of the same name took issue with Seton using what they felt was their title). Seton later credited it as the first in a decades-long series that became known as The Birch Bark Roll.

Primarily intended for a white boy audience, actual Native Americans have taken issue over Seton’s claim of creating something in “True Indian Style.”

Philip J. Deloria

The historian Philip J. Deloria (Professor, Harvard University) took on the broad category of Playing Indian in a 1998 book. Heading for its 25th publication anniversary next year, Dr. Deloria’s work remains essential reading on the creation of white American identity vis-à-vis the interaction of European invaders with indigenous peoples. Differentiating this professor’s work from that of other writers is that he has largely foregone political polemic in favor of a scholarly treatment of the subject. Which is not to say that he is disapassionate. For me, he is all the more powerful for explaining issues of identity not taken on by anyone else in quite the same way prior to the sharing of his research.

The Perfect Symbol

Playing Indian has a long history in North America, but also roots into a more distant past in Europe. Over centuries, anti-authoritarian rural Brits, for instance, wore disguises when protesting land use regulations including hunting restrictions.

“Disguise readily calls the notion of fixed identity into question. At the same time, however, wearing a mask also makes one self-conscious of a real “me” underneath. This simultaneous experience is both precarious and creative, and it can play a critical role in the way people construct new identities.” (Pg. 7)

The best known (although not the first) example of white people playing Indian in this country were the faux-Mohawks of the Boston Tea Party, vandals using a colorful method of tax protesting. The ethnic and even personal identities of the merry mob were of course known. But it is important to note that white men chose to merge their identities with those of Native Americans. In a way it was a joke, but at the same time it is important that they expressed their growing sense of Americanness through the use of Native costuming. Two-hundred and fifty years later this tradition of identity appropriation continues.

Deloria examines the ongoing identity crisis for whites following their contact with the Indian (and “Indianness.”) The perceived freedoms and savagery of Native people contrasted with the logic and social order beliefs of Enlightenment-minded Europeans. This led to, in the words of D. H. Lawrence: “The desire to extirpate [him]. And the contradictory desire to glorify him.”

Enter Seton

Deloria continues: “…the practice of playing Indian has clustered around two paradigmatic movements—the Revolution, which rested on the creation of a national identity, and modernity, which has used Indian play to encounter the authentic amidst the anxiety of urban and postindustrial life.” (Pg. 7)

Deloria does not get to Seton until later in the book, but in his quote, we can see the genesis of Seton’s Woodcraft movement: In our rapidly urbanizing and civilized life (of the early 20th century,) Americans (with an initial emphasis on boys) are losing our regard for nature and the self-reliance inherent in experiencing the outdoor life. Looking back to the Old World for a model of dealing with this problem is a dead end.

Compare Deloria’s quote above to Seton writing in 1912 about his Woodcraft scheme: “To exemplify my outdoor movement, I must have a man who was of this country and climate; who was physically beautiful, clean, unsordid, high-minded, heroic, picturesque, and a master of Woodcraft…There was but one figure that seemed to answer all these needs: that was the Ideal Indian of Fenimore Cooper and Longfellow.”

Among the many questions this raises: How did Seton arrive at that conclusion in 1903 when he began his movement?

Seton As Follower, Not Innovator

In creating his Woodcraft movement with the generic “Indian” as its model, Seton followed a long-established tradition among white fraternal groups. “Tammany” societies of the 1700s found metaphoric inspiration in a 17th century chief of the Lenni-Lenape, Tamanend, famed for his civic skills. Groups such as the “Improved Order of Red Men” selected fake Indian identity (including dressing in Indian costumes and taking made-up Indian names and ranks) as a way to express (white) Americanness. Apparently, white participants saw no irony in this since in their view the real Indians were in the process of “vanishing” forever.

By the time Seton came along, white people had been engaging in these kinds of shenanigans for over a century and a half. He didn’t need to invent anything, simply latch on to these established traditions, applying them to boys in need of masculinization as a counterpoint to the urbanizing life that went along with capitalist industrialization.

As an aside here to those who focus solely on gender studies, Seton’s published writings suggest that he was anti-capitalist and a socialist (of a sort). That is, include in his motivations non-partisan generalized support for the political left as it existed during his life in the twentieth century, e.g. his ardent support of environmentalism.

Beneficiaries or Victims of History

Seton’s Woodcraft movement engendered enthusiasm among youth adherents in the American Northeast between 1903 and 1910 when it was subsumed into the Boy Scout movement. He spent over four years fighting for his vision of Scouting.

Seton lost the ideological contest. Robert Baden-Powell saw Scouts as serving the good of the nation state, while Seton believed in service to the community first. Personal attacks against him, however, often revolved around his commitment to understanding how the traditional values of Native America could inform and improve the lives of white Americans. That is, his admiration for the “Indian” was seen by his rivals such as Dan Beard as being somewhere between misinformed and downright crazy.

At the same time, some contemporary observers, including Native American writers, have characterized Seton’s admiration of the generic “Indian” as somewhere between being misinformed and downright racist.

And this, as Deloria points out, is an example of the larger issue of how white people deal with their take-over of the Native American world and how Native American’s respond to the trauma of the overtaking of their world by white people.

It Is So Obvious That Its not Obvious

Complicating matters still further were individuals such as Charles A. Eastman (Santee Dakota) who found much in common with Seton. Like Seton, he too, through lectures and published writings, sought to bring the values of the Red Man to the attention of the White Man. He sometimes appeared before white audiences in Sioux regalia, “But he was also—perhaps more compellingly—imitating non-Indian imitations of Indians,” according to Deloria. (Pg. 123)

The white Seton and the Sioux Eastman faced the dilemma of how to reconcile all those bad centuries of white-Indian conflict, including contemporary disorienting dilemmas of Americans (of all races) reconciling modernity with tradition while breaking with European history to find their own way. “The authentic, as numerous scholars have pointed out, is a culturally constructed category in opposition to a perceived state of inauthenticity.” (Pg. 101)

It is clear, as Deloria suggests, that neither Seton nor Eastman found a suitable resolution to centuries of sadness. The Gordian Knot of reconciling pre-modern with post-modern continues to confound. More work needed on that one.

And In The End

Playing Indian continued in the years after Seton’s 1915 departure from Scouting. He reconstituted the Woodcraft League which sputtered along before fizzling out not long after his death in 1946. More successful in the realm of playing Indian was the Camp Fire Girls, a Woodcraft oriented organization that has survived in modified form to the present. For their part white Boy Scouts created an “honorary” society, The Order of the Arrow, a colonizing of indigenous cultures that continues to this day.

“If it seems strange to find Indians haunting…the honor society of the Indian-free Boy Scouts, it is also completely consistent with a long thread of American practices.” (Pg. 127)

So what to make of Seton after all this? Deloria describes Seton as a “cultural mediator” and “upper class reformist” who “bridged implacable social, racial, and temporal gulfs between Indians and modern non-Indians” to, in part, support traditional gender roles (Pg. 129, 187.) Deloria does not assign a good or bad value to this, instead offering up Seton (and others in the book) as part of the American continuum through which white people have attempted to find their own identity in relation to “Indianness.”