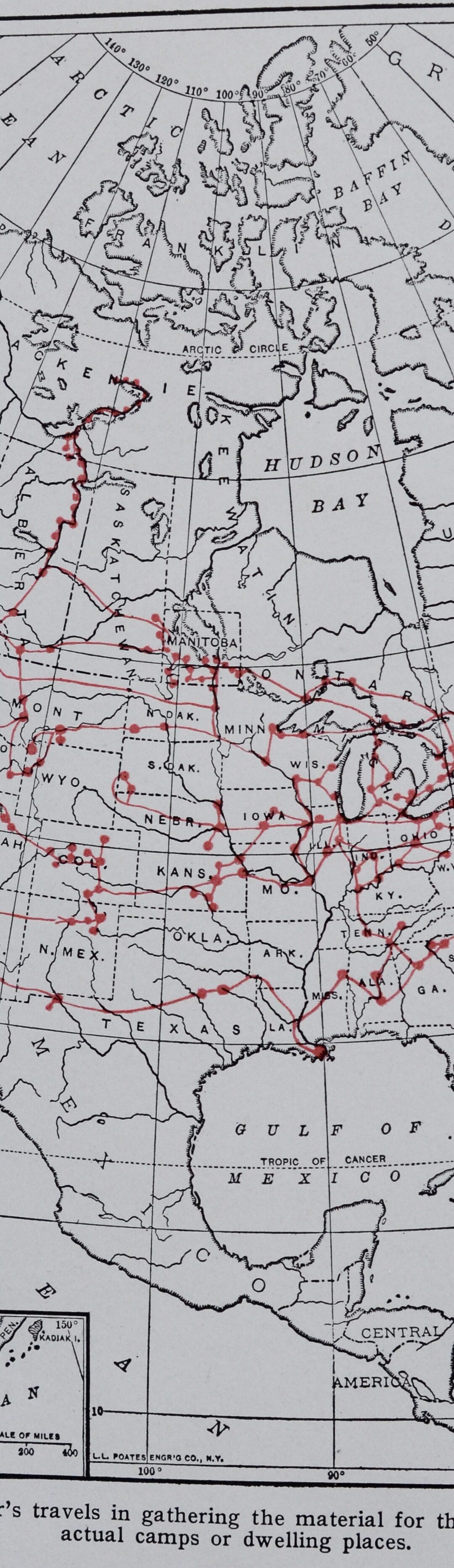

Seton’s Travels illustration from Life-Histories of Northern Animals

Between 1903 and 1907 Seton found himself mired in a controversy not of his own making. John Burroughs began what came to be known as the “Nature Faker” scandal in which he alleged that three writers (including Seton) fabricated stories about nature. I have examined this in detail in a series of four blogs in the Guest Writers section. Much of the criticism of Seton by Burroughs and Theodore Roosevelt was misplaced due to their lack of knowledge about animal behavior. This deeply wounded Seton who admired both of his attackers.

He ended up taking this as a challenge, changing his focus from fiction about animals to an encyclopedic non-fiction presentation in six massive zoology volumes, Life-Histories of Northern Animals, An Account of the Mammals of Manitoba (1910) and Lives of Game Animals, An Account of those Land Animals in America, north of the Mexican Border, which are considered “Game,” either because they have held the Attention of Sportsmen, or received the Protection of Law. (1925-1928).

Foreword to Life-Histories

Seton went to great pains (and only one sentence break!) to position the two volumes of Life-Histories as science based, clearly in direct response to the nature faker allegation.

“This aims to be a book of popular Natural History on a strictly scientific basis. In it are treated some 60 quadrupeds that I have known and studied for many years…Thirty years of personal observations are herein set forth; every known fact bearing on the habits of these animals has, so far as possible, been presented, and everything in my power has been done to make this a serious, painstaking, loving attempt to penetrate the intimate side of the animals’ lives—the side that has so long been overlooked, because until lately we have persistently regarded wild things are mere living targets, and have seen in them nothing but savage or timorous creatures, killing, or escaping being killed, quite forgetting that they have their homes, their mates, their problems and their sorrows—in short, a home-life that is their real life, and very often much larger and more important than that of which our hostile standpoint has given us such fleeting glimpses.”

Lives of Game Animals

Fifteen years later, in Lives, he continued the practice of sharing his personal observations, the observations of others, up-to-date science, and creating his own technical illustrations and range maps (something of an innovation). He estimated populations based on both distribution and habitat, an approach later made mainstream by MacArthur and Wilson. Seton, the self-described artist-naturalist, could combine many different approaches—no other one author could do so. He incorporated material from Life-Histories (often word for word) before adding new further observations. In both sets, he gave many indigenous names to the animals he studied, crediting the First Nations and Native American informants.

Additionally, Lives ramped up the conservation message including graphic descriptions of the pointless slaughter of wildlife. New sections included lyrical descriptions about the daily lives of creatures in the wild, a precursor to today’s nature films. He also included—as a condition of publishing the series—“Synoptic Line Drawings” distinguishing his work from that of anyone else. These drawings, often whimsically dark, show the triumph and tragedy of wild animals in relation to their environment and to the depredations of humans.

Seton’s reputation is largely based on his fictionalized stories about wildlife and his foundational work in youth education (including Scouting). Concurrently, over a span of about twenty-five years, Seton dedicated his prodigious talents to the creation of these monumental works. They are less well known today than should be the case for they are a wonderfully original telling of nature’s story.