Kit Fox and His kingdom (All image rights to Seton artwork reserved by the Academy for the Love of Learning. Click images to enlarge.)

A single photograph can capture a limited amount of information about an animal and its environment. The drawing medium, however, can capture much more. Seton created “synoptic” (summary) drawings, one for each of the hundred or so species featured in the massive, four-volume compendium, Lives of Game Animals (1925-1928).

I wrote about them in Ernest Thompson Seton, The Life and Legacy of an Artist and Conservationist. Today I couldn’t come up with a better statement than the one from that book:

“Seton accomplished something remarkable and daring in these drawings. His animals often wear expressions of joy or triumph; the drawings are not infrequently humorous in tone. They are a representation—based on Seton’s decades of experience—of animals overcoming seemingly impossible odds in order to live. The drawings are inherently ecological; that is, they express the notion of an animal living as part of the environment, a connection that is at once both physical and spiritual.”

These would have made a powerful exhibition had they remained together as a set. The Academy collection contains only a few of them. Seton went to a great deal of trouble to produce them. The publisher of Lives didn’t want to include them, but Seton insisted that if he couldn’t show them, he didn’t want to do the book.

The images shown here are from the Academy collection. See one more from this series, Wildcat Walking Warily, elsewhere in the Gallery section.

Kit Fox and His kingdom (featured image)

Kit Fox a.k.a. Swift Fox (Vulpes velox). This diminutive creature “no larger than a house cat” is a terror to mice and insects. Writing about them in Lives of Game Animals Seton worried about their future survival. A resident of the arid American West, they are threatened by habitat loss among other challenges.

The rolling wheels are ollins, a universal symbol of movement and change, used by a number of cultures worldwide over vast stretches of time. I believe that Seton intended it as a reminder that nature itself is change.

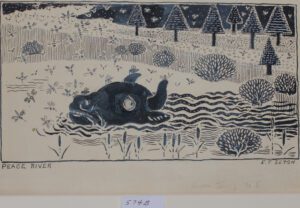

Peace River

Wood bison (Bison bison athabascae)

The Peace River flows through British Columbia and Alberta as part of the vast Mackenzie River system. Seton passed through the area in 1907, nearly losing his life while looking for the Wood Buffalo. The Canadian government created a National Park in 1922 to preserve this creature. Indigenous peoples living there at the time (Cree, Dene, and Métis) were evicted—notwithstanding their competent management of the area from time immemorial. A better record than that of subsequent managers.

Special note: During the other most dangerous parts of the 1907 expedition, into the Barren Lands of the Northwest Territories, Seton and his colleague Edward Preble were accompanied by two essential Métis guides, Billy Loutit and Louison d’Noire (“Weeso”). The Academy’s Aylmer Lake expedition revisited that area in 2015.

Seton intended irony in his illustration. Due to the mosquitoes—which plagued his entire Arctic trip—the one thing he did not find on the Peace River was peace.

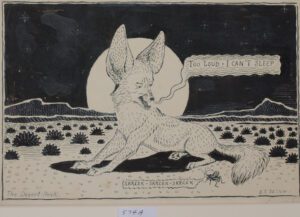

Too Loud I Can’t Sleep

Desert Fox (Vulpes macrotis)

https://www.foxesworlds.com/swift-fox/

The large ears of this smallest of North American foxes apparently give it a particularly strong sense of hearing. If you have visited remote deserts on windless nights, you will know that the inherent silence can be overwhelming. A single cricket would indeed make itself known, even for creatures such as ourselves that have limited hearing compared to the fox.

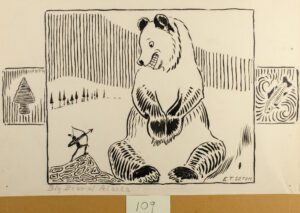

Big Bear of Alaska

Alaska Peninsula brown bear (Ursus arctos middendorffi/horribilis)

Based on his illustration, stories of this salmon eating giant must have impressed Seton. He had encountered Grizzly bears in Yellowstone National Park, but his travels, rather surprisingly, never took him to Alaska. Seton got rather too close to the ones he studied. For the rest of us: don’t do it!

Seton noted that he did not see the fabled Barren Lands Grizzly: “In 1907, when I entered the region as far as Sussex Lake, Headwaters of Back’s River, I found no trace of the species.” He should have been with me during my 2015 visit to Aylmer Lake.

Our expedition made camp on an Aylmer Lake beach, a short walk from Sussex Lake and close to, or in about the same spot where Seton stayed overnight during his visit. Not far from my tent were impressions in the sand of mother and cub Barren Lands Grizzly, with matching small and large scat piles, made the previous night. While much smaller than the Alaskan Brown Bears, they are said to be even more fierce. Sand mounds and dense willows would have hidden the bears from our sight even a short distance away. We did not encounter the Grizzly family, but I did not pass a particularly restful night.

See the really big ones here on a live and highlighted bear cam.

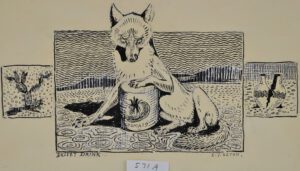

Desert Drink

Mearns’ coyote (Canis latrans mearnsi)

Seton identified this coyote, a resident of the desert, as a separate species. Biologists currently identify it as a subspecies based on its smaller size and slightly more colorful coat. How do they manage to live in a dry hostile environment? Seton wrote in Lives of Game Animals, “It must be remembered as an axiom, given food enough, most animals are indifferent to climate, and this is not only true of the Desert Coyote, but possible of a still larger interpretation, for given succulent food enough, the desert animal can commonly dispense with water.”

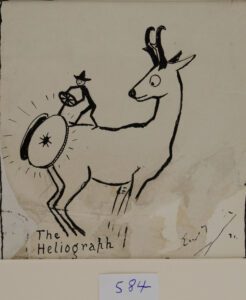

The Heliograph

Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana)

This illustration does not appear in Lives of Game Animals, but it is the one with have in our collection. Although they live on the plains, they are browsers not grazers, that is, they eat shrubs (such as sagebrush) and forbs more often than grass.

For those of you not current on antique military technology, a heliograph was used during the 19th century to send Morse code signals into the sky and could be read over long distances. The bright flashes of code were created by using direct sunlight. Not so good on cloudy days I suppose.

The Pronghorn uses their version of this signaling device—white rump hair—to alert other members of the herd to danger by a quick flash. Seton’s explanation:

“It is composed of hair graded from short in the centre, to long at the front edges. Under the skin of the part is a circular muscle by means of which the hair can, in a moment, be raised and spread radially in two great blooming twin chrysanthemums, more or less flattened at the centre. When this is done in the bright sunlight, they shine like tin pans, giving flashes of light that can be seen farther than the animal itself.”