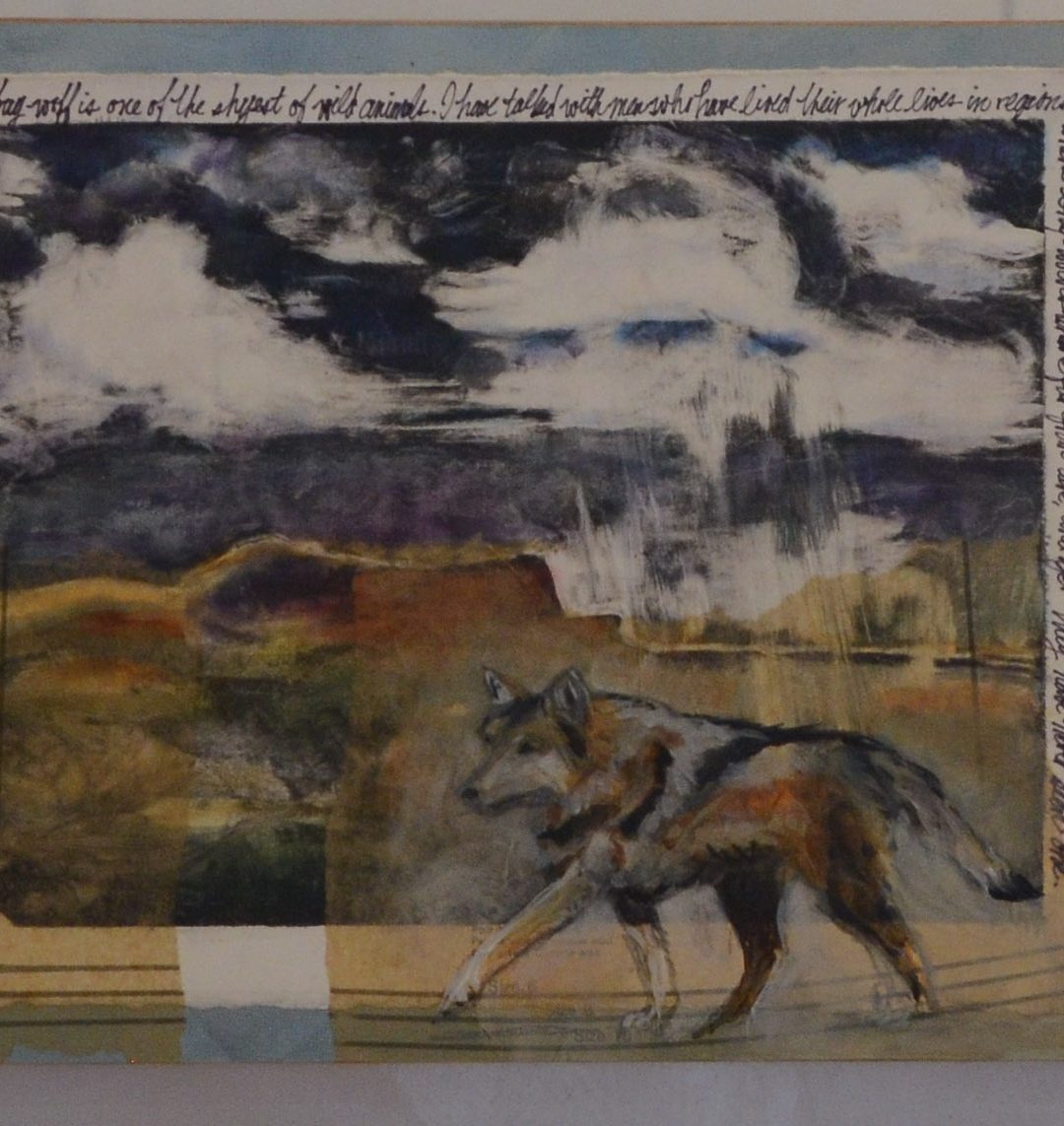

Amy Flowers, Eat, Prey, Love, Acrylic mixed media/2019

“More Beautiful and Amazing” Seton Gallery exhibition 2019-2020

The way of the wild is restless. Seton’s animal stories present a word portrait of the individual characters making their challenges and triumphs a matter of deep emotional involvement for the reader. One rabbit may look much like the next, but to take one example, the experiences of “Raggylug” in Wild Animals I Have Known, while common to rabbit-kind, are also his alone. His mother, Molly, teaches him the foot thump code known to all rabbits, but their ability to avoid foxes and dogs comes both from instinct and the experience of individual learning. Those who chase and for those who are chased are both individuals and joined units in forever interdependence. The three panels of this work by Amy Flowers shows this relationship—the three images are separate but connected as part of a larger mosaic.

Amy Flowers and Wildlife

Born an artist, I am self-taught with the privilege of having several gifted mentors throughout my artistic career. Primarily a painter, I began working with watercolor in my teenage years. Early work was created in a traditional, realist style using pastel, charcoal, pen and ink and moving into watercolor. About 20 years ago I began experimenting with alternative art media; this experimentation led to the use of acrylic paint, inks, collage and the development of a more abstract vision.

My work is energetic and vibrant, and I paint using multiple thin layers of acrylic to achieve the glow and depth that my pieces are known for. Acrylic is worked under and over the collage elements, fusing the paint with objects and ephemera. Inspired by natural color, form and the little details that surround us, I paint to express the energy and joy I find in everyday adventures and environments.

“Eat, Prey, Love” was created as a response not only to the process and influence of Seton and his work on my own studio practice, but as a contemporary reaction to what we have lost in the modern world. I grew up reading about the era of abundance in North America, imagining the Great Plains dark with herds of buffalo as far as the eye could see, landscapes raw and unsullied by the approaching Industrial Age. I memorized images recorded and painted by early artists and explorers of the West while filling up my own sketchbooks, drawing and painting, pretending to be the grand explorer in my own little patch of backyard woods. The thrill of spotting any wildlife was considered a privilege, a lucky find—unlike the history I was reading about. “Eat, Prey, Love” reflects that same thrill I had as a kid, seeing that one solitary animal in the wild, while realizing it shouldn’t be the only creature left standing in the landscape.

Ernest Thompson Seton and the Tragic End for Animals

For the wild animal there is no such thing as a gentle decline in peaceful old age. Its life is spent at the front, in line of battle, and as soon as its powers begin to wane in the least, its enemies become too strong for it; it falls. There is only one way to make an animal’s history un-tragic, and that is to stop before the last chapter. (Lives of the Hunted, pg. 10, 1901)

(Eat, Prey, Love, copyright Amy Flowers, used by permission)