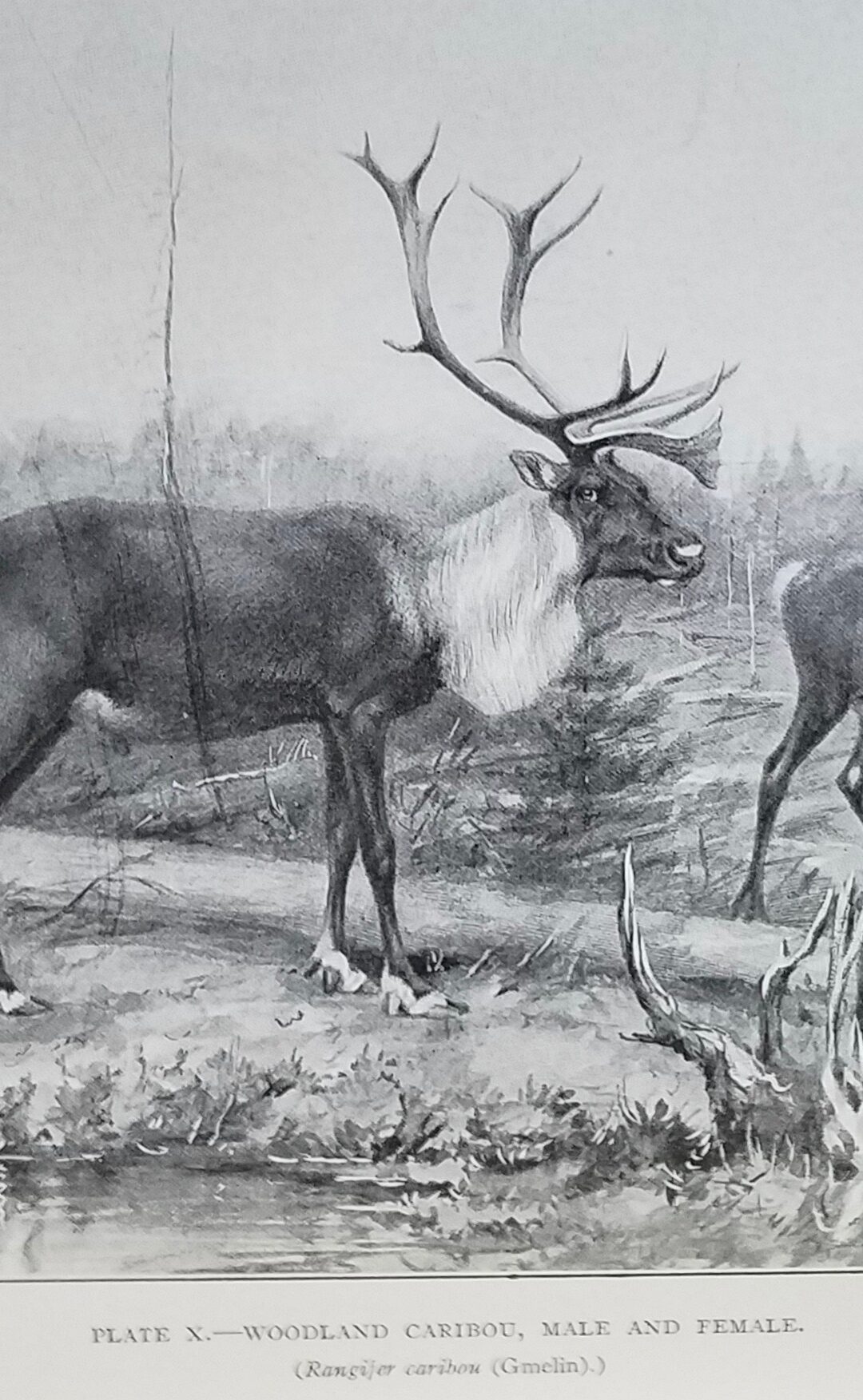

Woodland Caribou, Male and Female, by Ernest Thompson Seton

(This is an excerpt from Life-Histories of Northern Animals by Ernest Thompson Seton. Published in 1910, Seton chronicled the lives of 60 species in a massive two-volume work including ecological and behavioral information and innovations such as range maps. Given the limitations of the blog format, I am presenting only a small part of what he wrote about each animal. I have applied very light editing in a few instances.)

The Woodland Caribou or American Reindeer. Rangifer caribou Gmelin. (Rangifer, made up by Hamilton Smith in 1827, apparently from old French, Rangier, a Reindeer, and the L. fera, a wild beast (Cent. Dict.); caribou, the New England Indian name.) French Canadian: le Caribou. Cree, Saut., & Ojib: Ah – tik. Chipewyan: Et-then. Yankton Sioux: See-hah Tang-kah.

(Pg. 196) The Woodland Caribou is found all winter in small bands of both sexes. Five to twenty are commonly seen together at this time. Thus the species is quite gregarious, yet is but slightly sociable, since individuals rarely combine their efforts for a common purpose.

A gregarious animal has usually many means of communicating with its fellows. In this case, the well – marked livery of the species serves as his uniform does a soldier; it lets friend and foe alike know who this is.

Next in importance is the “white flag,” the tail and its surrounding disk, with which, as in most Deer, the Caribou does its wigwag signaling. The sudden elevation of this white tail when danger is sensed, conveys at once a silent alarm to the nearest of its kind. Probably the white patch of hair on the throat is used much as the Antelope use their disk, that is, as a flash-signal.

The Hoof Clicks

(Pg. 197) The most singular, perhaps, of the sounds made by the hoof Caribou is the clicking or creaking of the hoof. At each step each foot gives out a loud, sharp crack.

This is easily heard at a distance of fifty feet in a wind, and twice as far in still weather. When a herd is moving along the countless crackles from their hoofs make a volume of low, continuous sound.

Persons who have never heard this curious clicking have no difficulty in explaining it: “Of course the hoofs spread when they bear the weight of the animal,” they say, “and, when lifted, the hard surfaces spring together with a ‘ crack.’” But close observation shows that the crack is made by some mechanism in the foot, and that it “goes off” while the weight is on it.

It is not always one sharp crack, but sometimes a crackle, or several little sounds close together. Many examinations made in Norway and in the Winnipeg Zoo have shown me that the crack takes place just as the foot is relieved of the animal’s weight, but before any part is lifted from the ground. The hoofs do not strike together during the stride, and the crackle is not heard until the foot is placed, and the weight is on it. Thus it may crackle twice at each tread, always once as the weight is coming on; usually a second time as it is going off. I have walked many times on hands and knees by the side of the Reindeer to make observations. On one occasion I induced one to walk beside me while (at considerable personal risk) I kept my hand on the knuckle – joint of his hind – foot. The crack took place each time with the bending of the knuckle joint. It was so violent that it jarred the hand laid on it. It was deep – seated and on the level of the cloots or back hoofs. Apparently it was made by tendons or sesamoids slipping over adjoining bones.

The object of this curious sound is, doubtless, the same as that of the whistling of a whistler’s wing or the twittering of birds migrating by night. It is to let the rest know what is doing – that the band is up and moving – has gone such and such a way, or to notify the little one that his mother is on the march and that he should keep alongside.

Caribou vs. Seton

(Pg. 202) In character, this creature is a strange mixture of wariness, erraticness, and stupidity. One never knows just what the Caribou is going to do next, but may be sure that the animal is going to do it with amazing energy and persistence. Its sense of smell is exquisite, and its eyes and ears are good, but it relies mostly on its nose.

I once had an adventure with a Caribou which, though slight and unromantic, might have cost me my life. It illustrates the uncertain temper of the animal and the energy with which it can act on occasion:

About 1889 someone in Maine offered [P.T.] Barnum a fine bull Caribou. The genial showman at once secured this animal, which, though so common in a wild state, is rare in menageries, and brought it, wild – eyed and sullen, to Madison Square Garden, New York. As soon as I heard of its arrival I wrote for permission to make some notes. Receiving this, I went to the Garden. The keeper in charge was as sulky as the prisoner. The letter of the Manager barely secured attention.

“ You’ll find him there,” and he jerked his head toward a dark stall.

“ That won’t do,” I said, “I am here to sketch him, and must see him.”

“ Well, suit yourself. ”

Proceeding to do so, I got a long rope halter on the creature’s neck. The keeper, seeing me about the risky business of leading the Caribou into the ring, and knowing that he would be held responsible, got another long halter, and together we brought the animal out where he could be seen.

There was nothing to tie him to, so we had to stand holding the ropes and be ready to pull in different directions. In order to have my hands free for sketching, I tied the rope around my waist. Soon the keeper got very weary of his task. The clowns in the next ring were practicing for the afternoon performance and he turned to watch them. The Caribou seemed to see its chance. Giving a great bound it jerked the rope from the keeper’s grasp and dashed the length of Madison Square Garden, dragging me by the rope which was tied about my waist. I rolled over many times, but, after about 50 yards, got my heels into the sawdust and my hands on the rope. The circus people did nothing but laugh and cheer as the powerful brute lunged along; but the keeper, realizing that he was laying up trouble for himself, came to the rescue and caught the end of the other rope.

Whereupon, the Caribou changed his behaviour and stood perfectly still, with head down, as though he were quite a different animal.

[Ed. Note, October 2021: This species currently listed as Rangifer tarandus caribou, consists of several subspecies and numerous scattered populations. All Caribou are under threat from climate change, hunting, and habitat loss including tar sands mining, in addition to forest fires from natural and human sources.]