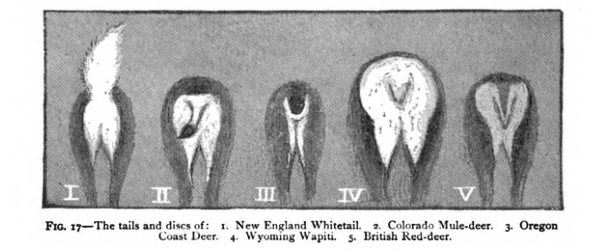

The tails and discs of deer by Ernest Thompson Seton

(This is an excerpt from Life-Histories of Northern Animals by Ernest Thompson Seton. Published in 1910, Seton chronicled the lives of 60 species in a massive two-volume work including ecological and behavioral information and innovations such as range maps. Given the limitations of the blog format, I am presenting only a small part of what he wrote about each animal. I have applied very light editing in a few instances.)

The Northern Whitetail, Northern Whitetailed Deer, or Northern Virginian Deer. French Canadian: le Dain fauve à queue blanche; le Chevreuil; le Cerf de Virginie. CREE & Ojib.:Wab – ai – ush ‘ ( Whitetail ). Yankton Sioux: Tah – chah T seen – tay – skah. Ogallala Sioux: Tah – been – cha ‘ – lah (Deer). Odocoileus virginianus borealis Miller.

(pg.87) The greatest enemy of the Whitetail is the buckshot gun with its unholy confederates, the jacklight and canoe. I hope and believe that a very few years will see them totally done away with in deer sport – classed with and scorned like the dynamite of the shameless ” fish – hog. ” Next comes the repeating rifle of the poacher and pot hunter. The third enemy is deep snow. It is deep snow that hides their food, that robs them of their speed, that brings them easily within the power of the Cougar on its snow – shoes , and of the human Cougar who is similarly equipped for skimming over the drifts.

(A “pot hunter” kills wildlife for commercial food sale, i.e., “bush meat. dlw)

Life of the Doe

(pg. 96) If we begin in the early spring to follow the life of the Whitetail on its northern range, we shall find that up to the month of January the does and bucks are still in company. I think that both males and females are found in the deer yards throughout the winter, and that young bucks may follow their mothers throughout their first year.

But the melting snow sets all free again. The older bucks go off in twos or threes, leaving the does to go their own way also, which they do in small groups, accompanied by their year before. All winter the herd has fed on twigs, moss, evergreens, and dry grass. Now, the new vegetation affords many changes of nutritious diet, consequently they begin to grow fatter, and the unborn young develop fast. The winter coat begins to drop and a general sleekness comes on both young and old. May sees the doe a renovated being, and usually also sees her alone, for now her 63 months ‘ gestation is nearing its end. Someday, about the middle of the month, she slinks quietly into a thick cover, perhaps a fallen tree – top, and there gives birth to her young.

The mother visits them perhaps half a dozen times a day to suckle them. I think that at night she lies next them to warm them, although the available testimony shows that, in the daytime, she frequents a solitary bed several yards away. I suppose that she never goes out of hearing of their squeak, except when in search of water. If found and handled at this time the fawns instinctively “play dead,” are limp, silent, and unresisting.

Their natural enemies now are numerous. Bears, Wolves, Panthers, Lynxes, Fishers, dogs, Foxes, and eagles are the most dangerous of the large kind. But the spotted coats of the fawns and their death – like stillness are wonderful safeguards. Many hunters maintain, moreover, that fawns give out no scent. Doubtless this means that their body – scent is reduced to a minimum; and, since they do not travel, they leave no foot – scent at all.

The mother is ready at all times to render what defense she can to her fawn; and, unless hopelessly overmatched, she is wonderfully efficient. Her readiness to run to her young at their call of distress is (or was) often turned to unfair account by the hunters in the Southwest. They manufactured a reed that imitated the fawn’s bleat, and thus brought within gunshot not only the anxious mother, but sometimes also the prowling Cougar and Lynx.

Does A Mother Ever Forget?

Natural questions that arise are: Does the mother never forget where she hid her young? Can she come back to the very spot in the unvaried woods, even when driven a mile or two away by some dreaded enemy?

In the vast majority of cases the mother’s memory of the place enables her to come back to the very spot. Sometimes it happens that an enemy forces the little one to run and hide elsewhere, while the mother is away. In such cases, she sets to work to ransack the neighborhood, to search the ground and the wind for a helpful scent, listening intently for every sound. A rustle or a squeak is enough to make her dash excitedly to the quarter whence it came. It is probable, though I have no conclusive proof, that now she calls for the fawn, as does a cow or a sheep whose young are missing.

In most cases her hearty endeavors succeed. But there is evidence that sometimes the end is a tragedy — that the fawns, like the children of the story, are lost in the woods.

The Moose and the Wapiti may hide their young two or three days, the Antelope for a week; but the Whitetail fawns are usually left in their first covert for a month or more.

At this age their rich brown coats are set off with pure white spots , like a brown log sprinkled with snow – drops, or flecked with spots of sunlight . This makes a colour scheme that is protective as they crouch in the leaves, and is exquisitely beautiful when , later on , they bound or glide by their mother’s side to the appreciative mirror furnished by their daily drinking pool.

At four or five weeks of age — that is, about the beginning of July — they begin to follow their mother. I examined one, however, that was found hidden in the grass near Dauphin Lake, Manitoba, as late as the 22d of August.

Analogy would prove that the fawns begin to eat solid food at this time. They develop rapidly and become very swift – footed. Some hunters maintain that they are even swifter than their parents, but this is, I think , not the case . As already noted, it is a rule that, of two animals going at the same rate, the smaller always appears to be the faster.

A Day In The Life

Their daily lives now are as unvaried as they can make them. They rest in some cool shelter during the heat of the morning, and about noon they go to their drinking place.

This daily drink is essential, and yet the map shows the Whitetail of the far South – west to be a dweller in arid country where no water is. Here, like the Antelope , they find their water – supply in the leaves and shoots of the provident cactus , which is among plants what the camel is among beasts — a living tank – able to store up, in times of rain, enough water for the thirsty days to come.

The mother Whitetail, after a copious draught, sufficient to last all day long, retires again with her family to chew the cud in their old retreat, where they escape the deer – flies and heat, but suffer the mosquitoes and ticks. As the sun lowers they get up and go forth stealthily to feed, perhaps by the margin of the forest, where grow their favorite grasses, or the nearest pond, where the lily – pads abound, and root, stem, or leaf provide a feast that will tempt the Deer from afar. They munch away till the night grows black, then sneak back to some other part of the home covert, rarely the same bed, where they doze or chew the cud till dawn comes on. Then, again, they take advantage of the half – light that they love, and go foraging till warned by the sunrise that they must once more hide away.