At the time of his return from the 1907 Arctic expedition, Seton was a celebrity whose exploits were regularly covered by the press. The article which follows, covers the northernmost part of his Arctic adventure in an interview that took place not long after his return.

New York Times, November 24, 1907

Back at his beautiful country place, Wyndygoul, at Cos Cob, Conn., and feeling particularly at home again in civilized surroundings, Mr. Ernest Thompson-Seton is now able to cover once more, this time on maps, his recent trip to the Barren Lands of British Columbia.

“For all my family knew, during the last seven months, I might have been dead,” he told the Sunday Times man, who journeyed out to Wyndygoul to hear about the trip. “Whatever I learned about the outside world, and whatever the latter learned about me, was through what is known as the ‘moccasin telegraph,’ in other words, news communicated by one Indian or trader to another.”

Farthest North

Mr. Seton’s “Farthest North” was a point in the Barren Lands, on the shores of Lake Aylmer, hundreds of miles beyond the nearest trading post of the Hudson Bay Company. His course lay through a region which, in the past 150 years, has been penetrated by only five white men. Furthermore, while on the shores of Lake Aylmer, before turning back southward, Mr. Seton explored some regions hitherto untrodden by white men.

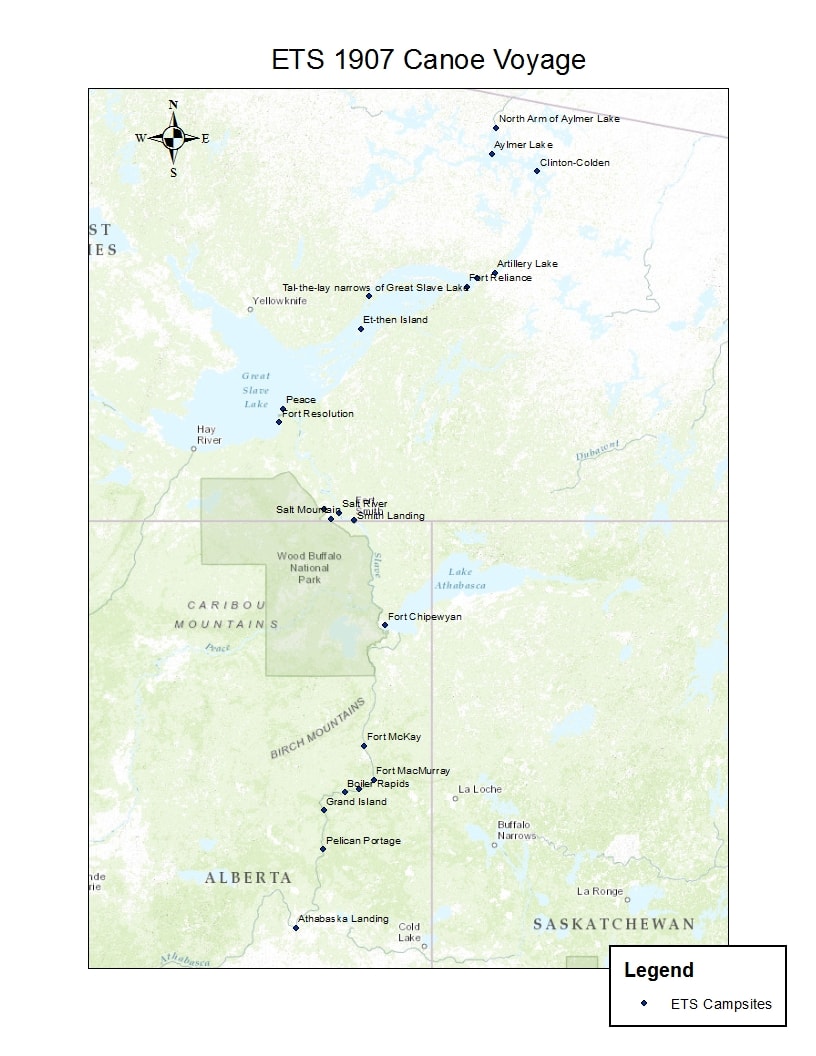

“I started away from civilization at Edmonton,” he began, when asked to describe his trip. “That is north of Winnipeg, and is reached by both the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific Railways. It is the jumping-off place. From it I drove to Athabasca Landing, on the Athabaska River, which I descended to Fort Smith.

“This preliminary part of my trip took over one month, from April 25 last to June 4.

“At Fort Smith I stayed about a month, making complete preparations for the continuation of my trip to the north.

Wild Buffalo

“In the region about Fort Smith is the last herd of wild buffalo on the American continent. Those in the Yellowstone Park are to some extent watched and protected. Those of which I speak are completely wild. The herd numbers several hundred head.

“I am glad to say that I was able to impress Earl Gray and the Canadian Premier with the desirability of protecting and preserving this herd. He has taken this matter up, and I have no doubt that the buffalos will henceforth be taken care of and allowed to multiply. Hitherto they have suffered severely from poachers.

“When we were thoroughly ready, I started north toward Great Slave Lake. The party consisted of myself, Mr. Preble of Washington [D.C.] who had been in these regions before, and two guides.

“People have no idea of the vastness of the rivers and lakes in the section of British Columbia which we now entered. The Mackenzie River is surpassed in length only by the Mississippi and the Nile, in width only by the Amazon. In some places it is two miles wide. One simply can’t see the horizon. Sky and water meet in the distance.

“And Great Slave Lake, on which Fort Resolution, where we next stopped, is situated, is 500 miles long.

Our Expedition Left the Known Route

“At Fort Resolution our expedition left the known route. I hired a sailing boat and a crew of nine Indians and proceeded northward across the lake. We were twelve days on the water, our next stopping place being Fort Reliance.

“Here our crew of Indians and their sailing boat turned back. I continued northward in my canoe, with Mr. Preble and [the] two guides.

“Our course now lay largely through lakes and streams which had never been mapped.

Aylmer Lake, in the direction of which we were heading, had been reached by only four expeditions, previous to mine. The last one to visit the region was that of Warburton Pike in 1889.

“We were now in the Barren Lands, a name given to the whole region north of this line.”

The explorer and his visitor bent over the map spread out before them. Mr. Seton traced a line north of the Great Slave Lake—a line which dodged in and out among mysterious rivers and big lakes.

“These,” he remarked incidentally, “are by no means accurately mapped. Some of them are just jotted down as if those who made the maps thought to themselves: ‘What’s the difference?—nobody will ever go there!’”

Then his finger stopped tracing lines from east to west, and resumed its northward course along the line of the expedition.

Caribou and Wolves

“In the Barren Lands,” he continued, “there is absolutely no timber. But the land is not desert land by any means. It is all rich prairie, and simply filled with game of many kinds, most especially caribou. These were seen everywhere along the line of our march. Besides, musk ox is plentiful; also wolves.

“These wolves are not much afraid of men. Once our cook went to get wood and on his return found a large wolf seated comfortably beside the fire.

“From the shores of Lake Aylmer I made several expeditions in different directions along routes unexplored before.”

“Did you make maps and surveys?” asked the reporter.

“Three volumesful,” was the answer.

But when asked to describe the exciting incidents of danger the explorer had surprising little to say.

“You see,” he explained, “ours was the best-prepared expedition that ever went into the Barren Lands. I had foreseen every emergency. To begin with, in seven month we covered a distance for which usually eighteen months are allowed. All along the route as we went northward, I left caches of food—usually in trees protected by waterproof coverings and raven scares—every one of which I found in perfectly good order on our return.

“Of course, we were stormbound here and there in crossing various lakes along our course but never in a way that was serious, and we did have some exciting adventures which I cannot now go into.”

Careful Preparation

Mr. Seton reiterated the fact that careful preparation had practically eliminated the usual hardships of expeditions such as his.

“We managed to get into the Barren Lands and out again,” he said, “without encountering snow on the ground. That in itself was enough to make the trip far easier than would otherwise have been the case.”

Then the reporter took up a point which had particularly impressed him in reading the first hasty accounts of the trip given by the explorer on emerging from the Northland—namely, the wonderful beauty of the scenery.

“It is not the idea which people have of the Barren Land,” the visitor remarked.

“Well, it is what struck me most about them,” declared Mr. Seton. “In general, the scenery reminded me of the most beautiful parts of central Wyoming. Time and again we waded waist deep in flowers and mosses.”

(Art work by Amy Lewis)