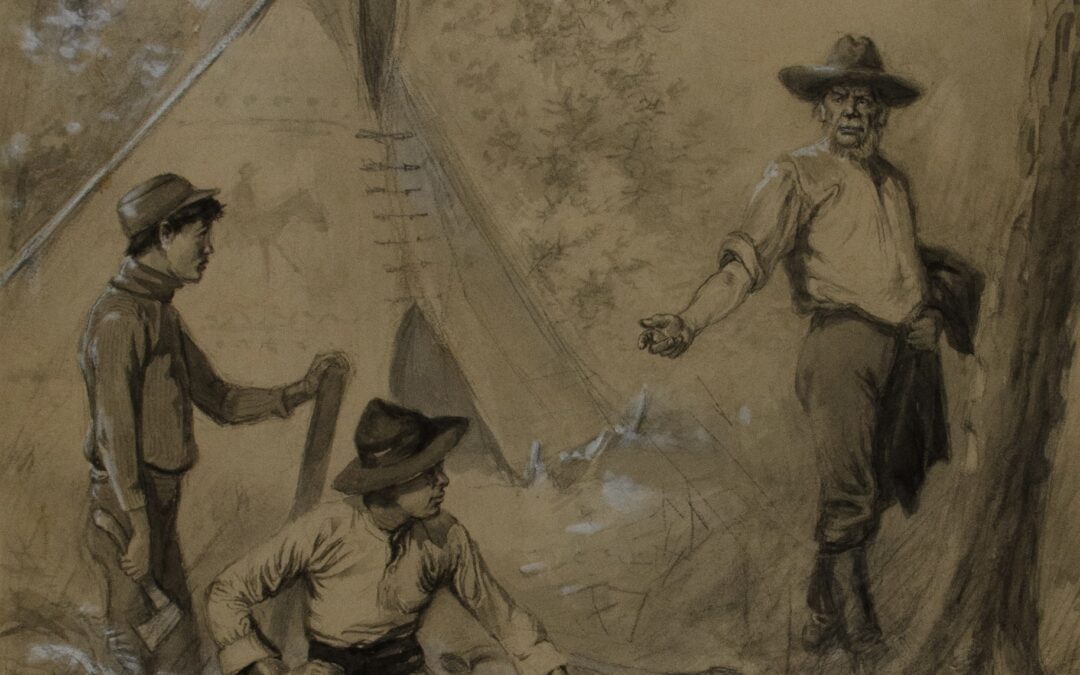

Illustration from Two Little Savages

For all that Seton has been largely forgotten by the general public, a small cadre of scholars and journalists continue to chart his legacy. While his nature-based work is usually viewed favorably, scholars who come out of Native American and gender studies have taken a more critical view. Seton’s appropriation of aspects of indigenous culture and his views of masculinity does not sit well with many contemporary observers.

Deciphering the consequences of Seton’s views of Native peoples is fraught with its own consequences, yet it is a subject that should not be avoided. One place to start is by listing several pivotal events in his life, concentrating on published work. We can chart his changing attitudes over time by the course of his own words. This is my initial attempt; more to be added as I fill out the history. (Some of the entries below are taken from Seton’s journals.)

Early Notations

1874 “I founded my Indian Tribe…with a definite program of outdoor activities…the Band died out after two years, but the idea did not.” (Trail of An Artist-Naturalist, p. 374)

1870s Seton reads The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757 by James Fenimore Cooper, likely sometime in his teen years.

1883 Meets Chaska (Cree) “I knew he could teach me much about woodcraft.” (Trail of An Artist-Naturalist p. 262)

1892 Performs “Indian dances” for the amusement of Ernest Blumenschein (future co-founder of the Taos art colony) and other artists in Paris. (The Taos Society of Artists, forthcoming book in 2023)

1897 August 29 – September 3, 1897 Visits Crow Agency, Montana. Meets retired U.S. Army scout White Swan (Crow) who provides him with drawings of Native American life.

1897-99 Begins serious study of Native American languages.

Woodcraft Makes Its Appearance

1901 Makes first purchases of “Indian curios.”

1901 “The Thought” pen & ink, first version, in Lives of the Hunted: nude white male on the verge of simultaneously destroying the generative powers of nature and himself. He later compares (unfavorably) white Euro-American society to that of indigenous North Americans.

1901 “Krag, the Kootenay Ram,” an allegorical story in Lives of the Hunted in which a white hunter is doomed by his obsession to kill a bighorn sheep. Scotty MacDougall, a brutal and spiritually bereft individual, is the stand-in for Euro-American society. Maybe the first environmentalist story.

1902 March Seton invites neighborhood boys to a weekend camping event at his Cos Cob estate. (By which time he had already begun writing a series of articles for Ladies Home Journal.) Seton does not note this camp in his journal, although he later tells and re-tells the story of its happening.

1902 May A series of articles, “The New Department of ‘American Woodcraft’” (a.k.a. “Ernest Thompson Seton’s Boys”) premiers in Ladies Home Journal.

1902 July “Playing Injun” article in Ladies Home Journal sets out activities for boys based on Seton’s claimed knowledge of the “Red-man” way of life. The article includes how-to sections on activities, Indian-themed gear, history, Seton’s own experiences, and a summary of cultural values of Native American peoples.

July 1 1902 Visits official first camp of “Seton Indians” at Summit, New Jersey. “Took a teepee also bows and arrows—had a wonderful time. More “tribes” quickly follow.

1902 July 14 – 23 Visits Pine Ridge Reservation.

1903 Publishes a pamphlet, Playing Indian, further explaining activities and use of Native American culture for a white audience. This is a forerunner of The Official Handbook for Boys (1911, Boy Scouts of America) and The Book of Woodcraft (1913). He terms this the first one of a series—The Birch Bark Roll—that will continue in various forms into the 1930s.

1903 Two Little Savages, Being the Adventures of Two Boys Who Lived as Indians and What they Learned. Best seller, still in print. Part outdoor how-to methods and procedures, part autobiographical novel with the boy Seton represented under the name “Yan.” Dialogue written in Canadian back woodsmen vernacular including use of racist language.

Changing Views

1911 Rolf in the Woods: the adventure of a Boy Scout with Indian Quonab and little dog Skookum. A novel featuring “Quonab, the last of the Myanos Sinawa,” companion, friend, guide and teacher to young white man Rolf Kittering during the War of 1812.

1911 The Arctic Prairies, A Canoe-Journey of 2,000 Miles In Search Of The Caribou Being An Account Of A Voyage To The Region North Of Aylmer Lake. Travelogue, observations of people (including First Nations), places, and wildlife. He is accompanied by the biologist and Arctic explorer Edward A. Preble and Mètis guides Billy Loutit and Louison d’Noire.

1913 The Book of Woodcraft and Indian Lore. A manual of outdoor education and values including a history section, “The Spartans of the West,” a repudiation of racist stereotyping of American Indians. Dr. Charles A. Eastman vetted this section “in regard to the character of the Indian.” “While I set out only to justify the Indian as a model for our boys in camp, I am not without hope that this may lead to a measure of long-delayed justice being accorded him. He asks only the same rights as are allowed without question to all other men in America—the protection of the courts, the right to select his own religion, dress, amusements, and the equal right to the pursuit of happiness. (p. vi., vii.)

1915 Order of the Arrow. According to Boy Scout leader Carroll A. Edson: “I attended a meeting where Ernest Thompson Seton gave a splendid presentation on the value he had found in using an idealization of the Indian, in his work with boys.” Inspired by Seton, Edson and E. Urner Goodman create an honorary society for their local camp; eventually the idea takes hold nationally to become part of the Boy Scouts of American official programming. Seton has no known involvement. This mostly white organization continues to use faux Indian costuming and aspects of Native American cultures in its ceremonies.

1917 The Preacher of Cedar Mountain. Novel. Protagonist Jim Hartigan lives on the frontier where the lives and beliefs of whites and First Nations people intertwine. Seton’s message-driven story touches on religion, feminism, and the ideal of the North American “West.” Native people outwit inept whites for a bit of comic relief while providing a model society based on sharing and community service.

Outcome of a Lifetime’s Work And Beyond

1918 Sign Talk, A Universal Signal Code, Without Apparatus, for Use in the Army, the Navy, Camping, Hunting, and Daily Life. Based mostly on “The Gesture Language Of The Cheyenne Indians,” Seton includes commonly used signs from other tribes as well as signs used in Europe and America at the time. “My attention was first directed to the Sign Language in 1882 when I went to live in Western Manitoba. There I found it used among the various Indian tribes as a common language, whenever they were unable to understand each other’s speech.” He is especially influenced by White Swan (Crow) who was disabled at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. “I was glad indeed to be his pupil, and thus in 1897 began seriously to study the Sign Language.” (p. v.)

1927 “A Lament On Visiting The Old Western Ranges.” A prose poem in which (among other things) Seton predicts that the greed of white people of North America will create environmental catastrophe, forcing survivors (if there are any) to abandon the continent.

1936 The Gospel of the Redman. A long essay in several parts: spirituality, traditional values, physicality, wisdom teachings, and history. This can be seen as Part II of “Spartans of the West.” “The Indian was a socialist in the best and literal meaning of the word.” (p.26) He claims to have shown the manuscript to several Native Americans: “Without their approval, nothing has been included in this book.” (p. vii.) Persons named: Chief Standing Bear (Sioux); Sunflower (Sioux); Walking Eagle (Ojibway); Ohiyesa, Dr. Charles A Eastman (Sioux); Ataloa (Chickashaw); John J. Mathews (Osage) and Chief Oskenonton (Iroquois). (p. vii-viii.)

1969 Custer Died for Your Sins. Vine Deloria, Jr., predicts the passing of the white man from North America after they fail to truly adapt to the land.

1998 Playing Indian. Philip J. Deloria. Ninety-five years after the publication of Seton’s title of the same name, Professor Deloria publishes a history of Indian-White relations.

For access to Seton books prior to 1927, see Hathitrust.

Thanks to LEC for suggesting the creation of this list.