On-line Copy of Original Article Illustration

Just in time for the annual Christmas Bird Count, here is Seton’s article that pushed Birding to new levels. When binoculars became available, so too new approaches to identification were needed. Seton provided a way into this new pursuit. Published in Bird-Lore pg. 187-189 November—December 1901 under one of the final times as “Ernest Seton-Thompson.”

RECOGNITION MARKS OF BIRDS BY ETS

In general the markings of animals are believed to be either protective or directive; that is, designed either to hide the animal, or else to distinguish it and make it conspicuous or ornamental.

PROTECTIVE OR DIRECTIVE

In the bird world we have many illustrations of both kinds of coloration in the same individual, for many species are protectively colored while sitting and directively while flying. Or, to put it in another way, the colors of the upper parts show chiefly when the bird is perching, and these are protective; the colors of the lower parts and expanded wings are directive, and are seen chiefly in flying. All birds with ample wings and habits of displaying them, bear on them distinctive markings; for example: Hawks, Owls, Plovers, Gulls, etc. All bird students will recall the pretty way in which most of the Plovers let the world know who they are. As soon as they alight, they stand for a moment with both wings raised straight up to display the beautiful pattern on the wing linings; a pattern that is quite different in each kind and that is like the national flag of the species, for it lets friend and foe alike know what species is displaying it.

On the other hand, birds like the Hummingbird, whose wings move too rapidly for observation, are without color pattern on the under side. These markings, no matter which category they belong to, are put on the bird first of all to be of service to its own kind. That is certain, as certain as the main truth of evolution; for, as Darwin long ago stated, if it can be shown that any species has acquired anything that is of use only to some other species, then the theory of evolution by natural selection must fall to the ground.

ACQUIRED CHARACTERISTICS

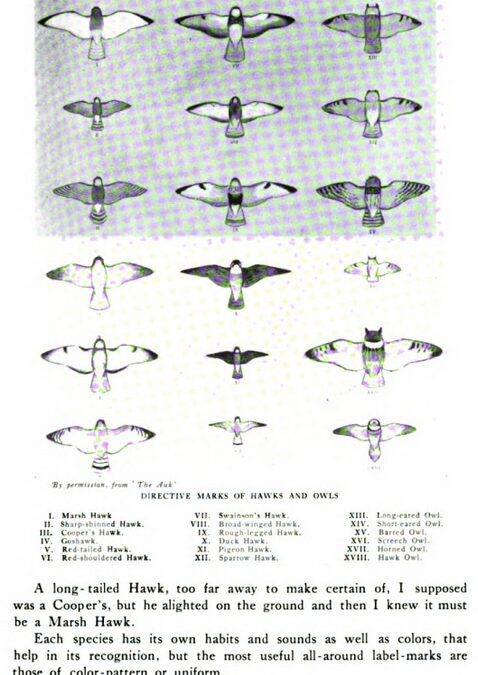

But this does not say that an acquired characteristic may not also be of use to another species. Thus the directive and recognition marks of the Hawks and Owls as illustrated on my plate are, of course, first to enable the birds of each species to recognize their friends, just as soldiers are uniformed so that each may know his own party. But the uniform also enables the enemy to distinguish him, so these recognition marks enable us to distinguish the birds at an otherwise impossible distance.

The directive marks of the common northern birds of prey are those selected for illustration. The size, shape and general color of the birds, as well as the spots, all enter into the plan. Those shown are adults; the young in many cases are different, but have nevertheless a recognized natural uniform which usually agrees in important features with that of its parents. Thus the white rump-spot is a constant and distinctive feature of the Harrier in any plumage. So is the white collar of the Horned Owls. The mustaches of Peregrine and Broadwing, and the wrist-spot, i.e., the dark splotch on the bend of the wing in the Buteo’s and in the tufted Owls, also the breast-band on Swainson’s Hawk and the body-band on the Rough-leg (see plate).

Late one evening as I walked through a marsh a large hawk-like bird rose before me. In the dim light I barely made out that it was a bird of prey, but as it went off I saw the white spot on the rump and that settled it beyond question as a Marsh Hawk or Harrier.

On another occasion I saw a bird in a tree. Its size and upright pose said Hawk. ‘On coming nearer its mustache marks said either Peregrine or Broadwing. But when it flew, the pointed wing and swift flight made certain that it was a Peregrine. Again a young Redtail sailed over my head in an opening of the trees. I took it for a young Goshawk, but before I tried to collect’ him I saw the wrist-spot that labeled him ‘Buteo,’ and so let him go.

THE USEFULNESS OF COLOR

The usefulness of the color-spots is increased by another well-known law, namely, that the peculiar feature of a species is its most variable feature. Thus the greatly developed bill of the long-billed Curlew, the beak-horn of the Pelican, the neck of the Swan, the collar of the Loon, are much more variable than features that they have in common with others of their group.

So, also, these markings are never twice alike. They keep the same general style but differ in detail with each individual, so that the birds can recognize each other personally, just as we do our friends by peculiarity of feature.

Of course color-spots are not the only things to be considered; pose, flight, voice, locality, probabilities and tricks of attitude all come in to help.

A long reddish bird darted past me to alight in a tree that almost concealed him. I thought it a Thrasher, but the deliberate pumping of his tail (another recognition mark), taken with his size and color, told me at once that it was a Sparrowhawk.

A long-tailed Hawk, too far away to make certain of, I supposed was a Cooper’s, but he alighted on the ground and then I knew it must be a Marsh Hawk.

Each species has its own habits and sounds as well as colors, that help in its recognition, but the most useful all-around label-marks are those of color-pattern or uniform.