I am seeking artists to take part in an exhibition slated for August 2020. Read on to learn about the organizing concepts behind “Endangered.”

Before the Land Ethic

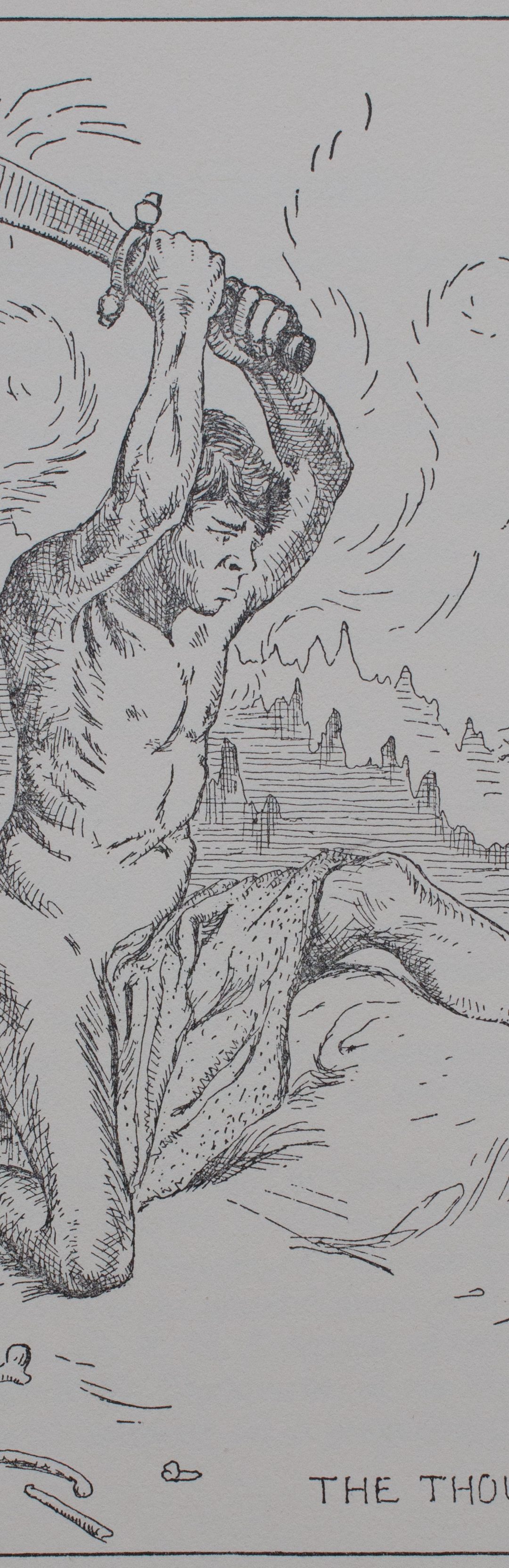

Decades before Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring or Aldo Leopold’s “land ethic,” Seton, through his art and writing, argued that our relationship to wildlife (and to nature generally) was essentially a moral one. In his important drawing, “The Thought” (1901 and 1924 versions) he graphically depicted the self-defeating result of our war on nature—by attacking the regenerative processes of nature, we do grievous harm to ourselves. In “The King of Currumpaw” (1894, about his final wolf hunt) and “Krag” (1901, about a doomed bighorn sheep hunt) he made the same point through the literary medium, creating the first environmentalist stories.

His stories about wildlife were often tragic in the outcome for the animal protagonists. At the same time, he implied that we humans could do better in our behavior, that through empathy with our wild relations, there was the possibility of salvation for both them and us: In return for their lessons to us on how to live, we owed them, our animal teachers, recognition of their right to exist, but also to thrive in their natural state. In his writing and lectures Seton called us to action to ensure their survival, launching the wildlife conservation movement and laying foundations for modern environmentalism.

Sixth Extinction

Then in 1927, during the writing of the monumental Lives of Game Animals, Seton took a darker view. Lives had been conceived as a compendium on the known facts about the larger North American mammalian species. His research also revealed the depredations and outrages committed against wildlife from the time of the 15th century arrival of Europeans. The mass exterminations might, in today’s terms, be thought of as a trial run for the Sixth Extinction as mammal (and bird) populations plummeted over the centuries due in large measure to pointless slaughter. (Here is a current list of North American mammals.)

Near the middle of over 4000 pages of natural history observations, he inserted an essay, “A Lament.” He established what might be thought of as a doctrine which he did not name, but one I would like to summarize as Endangered.

Endangered, as Seton saw it, began with our heedless disconnection of nature, our intentional (and perhaps even conscious) destruction of wildlife and the habitat in which animals live. Importantly, since Seton saw us as a part of nature, the loss of wild denizens, was just the beginning. Since we humans are not a-part from nature, loss accelerates over time, until in taking down wild nature, we take ourselves down as well.

Not just environmentally, but culturally and spiritually as well. While there is an increasing awareness of this among the environmentally-oriented today, look again at the dates—Lobo in 1894, Krag in 1901, The Thought in 1901, and A Lament in 1927.

Nature and Civilization (same thing)

Endangered, then is not just about wild nature, but also about the attendant societies, cultures, ethnic, religious, political and all other identities we assign to ourselves. Seton concluded with this, predicting our inescapable demise:

And on our last remembrance stone,

These wiser ones will write of us:

They desolated their heritage;

They wrote their own doom;

They knew not the things of the Spirit;

They never lighted the fourth lamp of the Woodcraft Altar fire.

Before I thought about “Endangered,” I described its manifestation in a separate essay as a loss of beauty—natural, cultural, diversity in all things and in all aspects of our life. I believe that Seton would have understood this definition.

I initially thought about creating an exhibition for the Academy’s Seton Gallery about endangered plant and animal species. But a conversation with Academy founder Aaron Stern on October 16th led us to define Endangered more broadly including human activities with those of wild nature, inseparable. That is, recognizing humans and our civilization as a part of nature, separating endangered societies from endangered species makes no sense. It is all a continuum.

As an example, we thought about the concept of building The Wall on the U.S.-Mexico border. Whatever one’s political views about the matter, The Wall creates a divide between wildlife populations (including traditional migration paths) as well as dividing long standing (and sometimes ancient) Latinx and indigenous communities. I believe that Seton’s A Lament was at its heart a treatise on the dangers of separation.

Last thought: Seton’s Fourth principle of Woodcraft was about finding within ourselves a place of absolute honesty and brotherhood, a place of the heart and of love on a deep level. (He referred to the campfire as both a literal and metaphorical place for this to take place.) Those who light this fire (literally while camping or figuratively within themselves) can banish the evils of our contemporary society from themselves including the tendency towards random destruction of nature and in so doing, find union with all humankind.

I suspect there will be much more to come on all this.