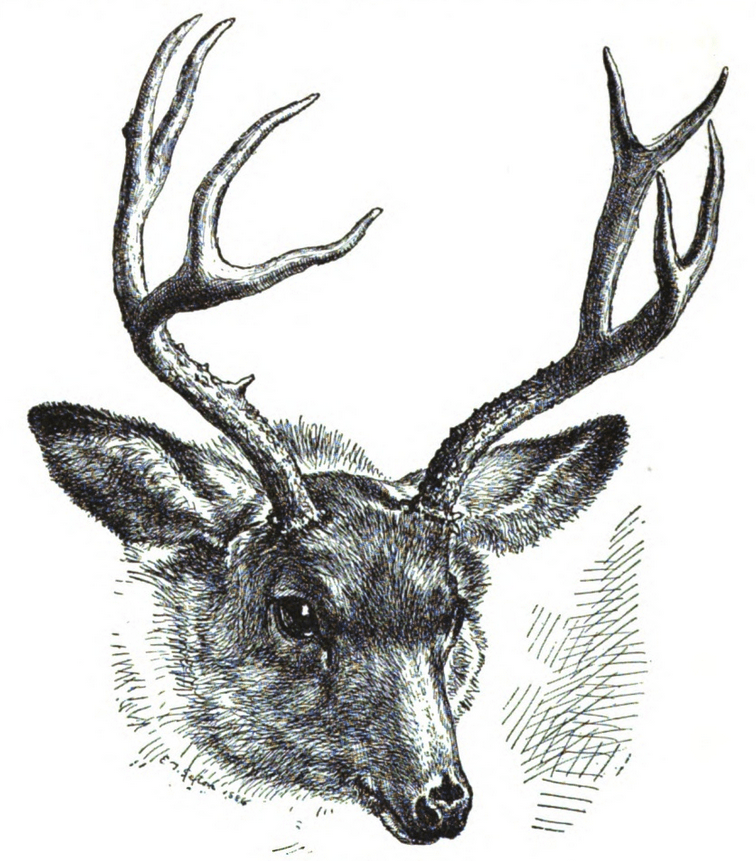

Young Buck, Carberry, Manitoba, December 1886 by Ernest Thompson Seton

(This is an excerpt from Life-Histories of Northern Animals by Ernest Thompson Seton. Published in 1910, Seton chronicled the lives of 60 species in a massive two-volume work including ecological and behavioral information and innovations such as range maps. Given the limitations of the blog format, I am presenting only a small part of what he wrote about each animal. I have applied very light editing in a few instances.)

Mule-deer, Mule Blacktail, Rocky Mountain Black tail, Bounding Blacktail, or Jumping -deer. Odocoileus hemionus (Rafinesque). FRENCH CANADIAN: le Dain fauve à queue noire; le Cerf mulet. CREE: Ap-is-chich’-koosh or Ah-pě-tchi-mu-sis’ (small Moose). Wood CREE & Saut: Muk-i- ti-wah’-no-wish ( black tail ). YANKTON Sioux, Tah-chah. OGALLALA Sioux, Tah-hen-cha’-la.

(Pg. 126) Let us begin to follow the Blacktail (Mule Deer) from the New Year’s Day of the Wilds. The mixed company of all ages and sexes that wintered together take advantage of the melted snow and better forage to scatter from the place where common interest in the food supply had kept them together. There is in particular a repulsion between the sexes: if two Deer go off together at this time they are two bucks or two does, but never buck and doe.

The association of pairs of bucks is a curious, well – known fact. Among the Red – deer of Scotland it is the rule for each big stag to have with him, all summer, a small stag as attendant or “squire.” This follower is said to do sentinel duty for his superior at all times except during the rut, when he is most unceremoniously driven about his business elsewhere. Whether any parallel to this exists in the present species remains to be seen. It is, of course, quite common to see two bucks living together all summer, and one is usually bigger than the other, but observations are lacking to explain their relationship.

Doe and Fawns

The does become still less sociable as the May moon wanes, and are now to be seen feeding and living alone. Grass and twigs are their staple foods, but there is little of vegetable origin that they will not eat. They drink twice a day, morning and evening. They are getting fat now and preparing for the great event of the year — the arrival of the young ones. This takes place in late May or in June. In some quiet woodsy hollow the 1, 2 or, rarely, 3 fawns are born. They appear in the white – spotted livery of true fawn – deer. It is like that of a young Whitetail, but the ground colour is duller, paler, and yellower.

The mother hides them usually at different points in the same thicket and comes to suckle them in the early morn and late evening for six or even eight weeks before she allows them to follow her. As late as July 30, in Manitoba, I have known the fawn to be hidden, though now well grown and probably seven or eight weeks old. The mother’s vigilance and devotion at this time are most admirable. Every possible danger is studied, and every creature that might injure her little ones is either fought or misled to the utmost of her powers.

(Pg.129) When I was at Marvine Lodge, Colorado, in September, 1901, I met several instances of the mother Blacktail’s devotion. One day a Red – tailed Hawk, wheeling low and whistling over the hillside, was fiercely watched by a mother doe, whose bristling rump-patch showed what she felt. Doubtless she took him for an eagle.

By the middle of August the fawns are following their mother, and now the spots on the coat have become somewhat dim. By the first of September in Colorado most of the young appear in the new uniform coat. On September 7, however, I saw two fawns still bearing well-marked spots. By the end of the month all the young except the very late ones are weaned and appear in the unspotted blue coat. They continue with the mother, however, and profit daily by her guidance and protection.

On September 28 I saw one in full blue coat, wandering alone and bleating piteously, announcing to all who heard that “here was a lost fawn”—an action not without its dangers, for a Lynx or Coyote was as likely to hear as the mother of the stray, and would understand the situation just as perfectly.

The Mule Deer in Winter

(Pg. 131) During winter the Blacktail continue in mixed bands of all ages and sexes, usually under the leadership of an old doe who is the great grandmother of most of them. In some favored parts of the country these winter bands become very large.

Their food at this time is twigs, browse, what ground stuff they can get by nosing and pawing under the snow, and what tree stuff they can reach by standing on their hind legs. The various tree mosses, beardy – mosses, and lichen are especially sought after.

Through the winter and spring the young follow the mother and get at least the advantage of wise leadership and example. When about a year old they leave her, probably because she compels them to do so, as an instinctive preparation for the new family. There is reason, however, for believing that the young does continue to associate more or less with the mother all through their second season.

Deer Keep Still

(Pg. 133) Every hunter learns, and every wild animal seems to know instinctively, the value of “freezing,” that is, becoming still as a frozen thing, when a stranger is discovered in the woods. The motionless object escapes notice and is better placed to notice others. The Mule – deer is an adept at freezing.

As I went through the woods at sundown I came on a doe. She was walking through an open place about 60 yards away, but she saw me just as I saw her. In fact, we met face to face. At the same moment we both froze and stood gazing, each waiting for the other to make the first move.

I waited three or four minutes at least, but she did not stir. Then it occurred to me to time her. I very slowly slid my hand up to my watch and stood as before, the Deer still watching me.

One minute — two minutes — five minutes went by, and still the Deer did not move. I began to wonder if I had not made a mistake after all, and watched a stump that had some what the form of a Deer. Then I thought, “No, I saw her walk there.” Six minutes — eight minutes — ten minutes passed and still the Deer stood.

“It is not possible,” I said to myself, “no Deer would stand like that for ten minutes. And yet there she is. That was plainly a Deer when it went there.” I waited another minute – still no move. “I’ll give her five minutes more, and if there is no movement I shall know I have been fooled by a stump.” Eleven and a half minutes, not counting the time before my watch was out, and there was a change, for it was a Deer that had been so intently watching me all the time, and it so happened that she now decided that she had been fooled by a stump. She changed her pose, turned to graze, and I had won the game of “freeze. “I brought my camera slowly to bear and snapped it, but the light was too poor to get a picture. The Deer now saw me move and bounded away.

The Bounding Mule Deer

(Pg. 140) There is nothing more poetic in four – legged speed than the flight of the bounding Blacktail.

Why these mighty bounds? Riding the Little Missouri hills, in 1897, with a company of wolf – hunters and followed by a pack of diverse dogs — trailing dogs, fighting dogs , and greyhounds, fleetest of their race to overtake the flying foe , we came by chance on a prey we sought not – a Blacktail mother with her twins. Great – eyed, great – eared, they stood at gaze, all three. We tried to turn our pack aside, but the greyhounds sighted game, and off like arrows shot they went, and the Blacktail turned for flight. We did our best to call the hounds away, but who can turn a greyhound from a foe that runs? Away they sped and the Blacktail sped away. How the memories of my youth came back as I watched them bounding along the level bottom lands, bounding – bounding – oh, it was beautiful, it was glorious, but it was sad!

For, notwithstanding all their wondrous powers, their wingèd heels, they were losing time. The greyhounds, far behind at first, were low skimming like prairie hawks, were making three yards to the Blacktail’s two, were gaining, went faster yet, were winning, would surely win. In vain we tried to ride ahead to cut them off, to turn or call them back; their speed, their mad impetuosity, grew only faster and fiercer. In spite of every effort, we knew that in a few minutes we should see three defenseless Blacktail mangled by our hounds.

The Chase

On and on the chase. The little ones were suffering now, were weakening. It was a question of barely a quarter mile.

Then we riders saw a thing that touched our hearts — that poor devoted mother, in despair, dropped back behind – deliberately it seemed — at least her young should have a chance, and my blood rushed hot. My hand sought the gun in reckless determination to stop those dogs. Only twenty – five yards ahead the mother now, when all at once an inspiration came. The unseen prompter whispered wisdom, and the mother turned aside, made for the rugged piling hills so near, she — all three soon reached their base and tapped with their toes, then rose in air to land some fifteen feet above, and tapped again – and tapped and tapped all three; and so they rose and sailed and soared. The greyhounds reached the rise and there were lost; their kingdom was the level plain; on the rugged hills they were helpless, balked, and left behind. But the mother and her two went bounding, soaring like hill – hawks, and so they sailed away till hidden in the heights, and safely at peace.

That day I learned the meaning of the bounding. These are the Deer of the broken lands; theirs is the way of the up lands; this pace is their gift, their power and their hold on life.