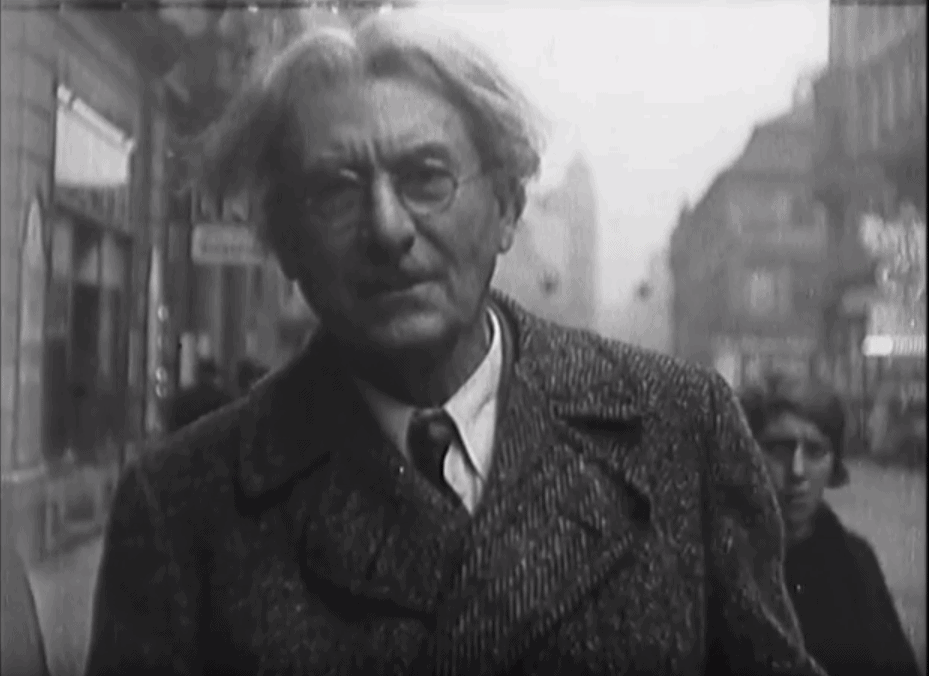

In days like these one can accept or assume no higher or better mission than that of peace messenger, a personal messenger of peace and understanding among the nations.

– Ernest Thompson Seton

This is a partial transcription from “Ernest Thompson Seton: A Scout Appeals for Peace,” broadcast on Radio Praha by the journalist David Vaughan in 2015. It is documentation of an original radio speech by Seton given during his European trip of 1936.

I have been unable to contact Vaughan, so I hope that he will not mind too much my sharing part of his broadcast with you. Eighty-two years later, the words still resonate. I don’t take this as a call for tolerance. Instead, it is a plea for acceptance, both for accepting the humanity and personhood of others, and for finding it within ourselves. Seton describes how he himself went through this process. Important to note is that in 1936 Seton was working on a monograph describing his interpretation of Native American ethics, The Gospel of the Redman. After stating his mission, he continued:

During the Great War many soldiers were taken prisoner by the opposing army. These prisoners were sent afar into military camps and prisons. They were fed, sheltered and, if wounded, had medical care. They had in short everything but freedom. Incidentally, they and their captors got acquainted, and although they had been taught to hate each other and to seek each other’s destruction, they now were subjected to other influences. They got acquainted, they began to understand each other. Understanding ripened into respect and respect into friendship. There can be no doubt that thousands of lifelong friendships were in that way founded during the war, all evidencing the great principle that understanding is the best remedy for misunderstanding.

Of course, such work would be less expensive and more effectual if brought about by peaceful activities, and this is the wise thought which is at the back of all such undertakings as international expositions, world tours, Rhodes Scholarships, Olympic Games, Peace Ambassadors and whatever tends to make foreign travel easy and contact with foreign countries the great privilege within the reach of all that have moderate means. If I may speak of my personal experience and observation, I have never yet known a man to go and live with a foreign nation without wholly reforming his previous concept of them, especially if that appraisal had been unfavorable.

Every American student who spent a few years in France or in Germany came back saying, “I have learned to love those French or those Germans now that I understand them.” Every Rhodes Scholar goes back from Oxford with a new and high appreciation of the old land and something like affection for its sterling qualities and even its eccentricities. I know of several men who spent years among the Negro tribes of Africa and came back in each case with a deep-rooted admiration of these so-called “primitives” and a real personal affection for many, if not all, of their black acquaintances.

Fifty-odd years ago I went West to live on the plains of America in contact with the North American Indians. I was attracted by the glamor that Fenimore Cooper and other romanticists had shared about the red man. And yet I was warned and distrustful, because of countless alleged histories of Indians’ cruelty, Indian massacres, Indian cold-blooded atrocities. I had to live with them many years and accumulate a library of thousands of records, talk with hundreds of old-timers, who knew the truth, before I learned that all these stories of wickedness and cruelty were pure fabrications, wicked slanders, invented by the white men to justify the invaders in seizing the Indian lands and dispossessing him of all his property, his gain, his horses, his liberty, as well as his home and children.

I came at last to the same conclusion as General Miles, Buffalo Bill and a score of outspoken leaders, who assured me that the Indian was the most heroic and noble type the world has ever seen.

Seton clearly saw himself as having been inspired by the Iroquois Confederacy, identified as the “White Roots of Peace” by anthropologist Paul A. W. Wallace. According to Wallace, and quoted by Seton in Gospel of the Redman, peace was attained through statesmanship, “by a profound understanding of the principles of peace itself. They knew that any real peace must be based on justice and a healthy reasonableness… Peace was not the mere absence of war…peace was the law…so inseparable from the life of man that they had no separate term by which to denominate it.”