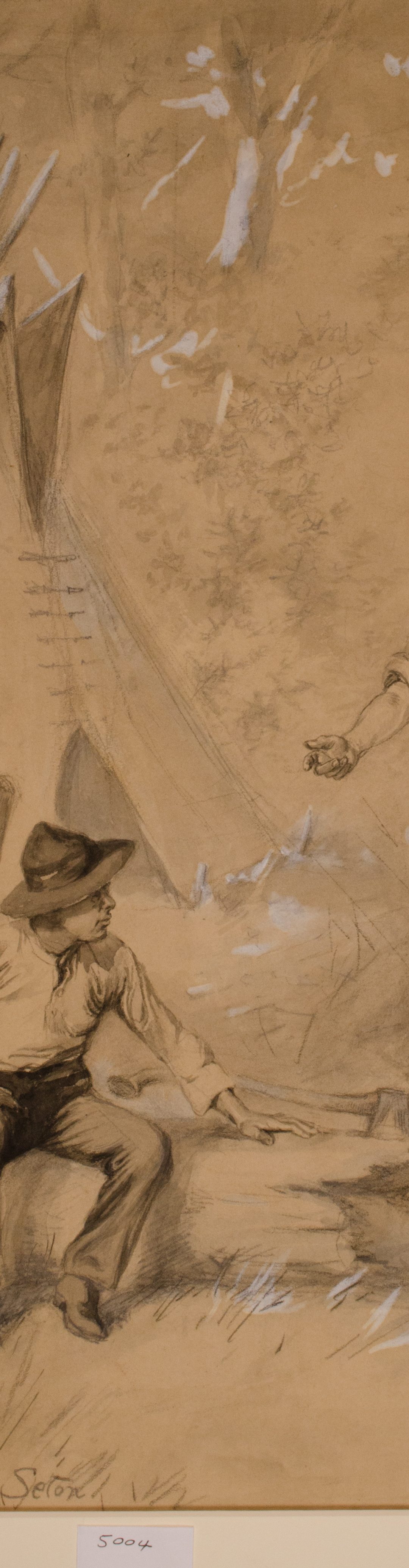

There is a wonderful passage in Two Little Savages (and yes, we can only wish that he had chosen a different title) where the adult Seton reflects on what the boy Seton was thinking in the 1870s (referring to himself as “Yan.”). He spent increasing amounts of time, generally alone, in the wilds of the Don River Valley, even building a “shanty” to live in (or at least visit) as part of the plan. He begins Chapter 8 just after having obsessed over finishing the little structure as the headquarters of his “kingdom.” With its completion, he at last could think in broader terms:

“His heart was more and more in his kingdom now; he longed to come and live here. But he only dared to dream that same day he might be allowed to pass a night in the shanty. This was where he would live his ideal life—the life of the Indian with all that is bad and cruel left out. Here he would show men how to live without cutting down all the trees, spoiling all the streams, and killing every living thing. He would learn how to do the same. Though the birds and the Fourfoots fascinated him, he would not have hesitated to shoot one had he been able; but to see a tree cut down always caused him the greatest distress. Possibly he realized that the bird might be quickly replaced, but not the tree.”

Here he reveals his fantasy about how “Indians” lived before the arrival of the white man. Unlike us immigrants from Europe, he understood North American aboriginal peoples to have lived as a part of nature with no need (psychological or physical) to destroy that very thing which nurtured them and the societies they had built. Trees, long lived and majestic, were especially important as representatives of all that is great and wonderful about nature. (Seton would later write a guide to eastern North American trees.)

In Seton’s telling—decades after “Yan” was grown—he had early on recognized his destiny as one who “would show men how to live” respectfully with nature. I think it more likely that recognizing his destiny likely came at a much later time. Nonetheless, his deep connection with nature was there from the beginning. And there was a next important step soon to come—learning how to pictorially depict what he was observing.