In 1907, after a life that had already included many great adventures, Seton embarked on one of his most important. At age 47 he made a five and one-half month canoe trip on rivers in Canada’s western Arctic. Accompanied by biologist Edward A. Preble, they began on May 18 and continued through their return at the beginning of November. Seton began publishing his results in the November 1910 issue of Scribner’s Magazine – the same publication that had made his career by publishing Lobo’s story sixteen years earlier.

Seton was still deeply hurt by the “Nature Faker” controversy of 1903 in which his credentials as a naturalist had been called into question by the lyric nature writer John Burroughs. He increasingly turned his attention to serious non-fiction including the 1909 Life Histories of Northern Animals and a full treatment of his expedition with Preble, The Arctic Prairies published in 1911.

The purpose of the 1907 trip was to explore an area above the Arctic Circle, especially the little known Aylmer Lake. The lake had been visited before but not mapped. Rumor was that the lake was as large as the gigantic Great Slave Lake (which is southeast of Aylmer). Aylmer Lake, at 847 Sq. Kilo., is connected by a narrow passage to Clinton-Colden Lake at 737 Sq. Kilo., but even taken together, the two are miniscule compared to Great Slave.

A Wonderful Adventure

No matter. Seton and Preble had a wonderful time studying plants and animals, climate and hydrology, and writing the first scientific and travel guide to that area of the Northwest Territories. Near the end of the trip a capsized canoe dunked all of Seton’s journals and maps into a river. The loss of all his notes would have been disastrous, but they soon turned up safe and dry. When he got back he slept in a building for the first time in almost half a year. He had experienced not one day’s ill health up until that time. After his first night inside he caught a terrible cold.

On August 20th, Seton wrote, “we camped in Sandhill Bay, the north point of Aylmer Lake and the northernmost point of our travels by canoe.” They hiked another six or seven miles north of the lake: “We had a most complete and spectacular view of the immense open country that we had come so far to see. It was spread before us like a huge, minute, and wonderful chart, and plainly marked with the processes of its shaping-time.”

Seton was euphoric and shared his excitement over several pages ending with: “This was the land and these the creatures I had come to see. This was my Farthest North and this was the culmination of years of dreaming. How very good it seemed at the time, but how different and how infinitely more delicate and satisfying was the realization than any of the day-dreams founded on my vision through the eyes of other men.”

Seton was clearly enthralled by the Arctic (excepting the mosquitoes). Unlike in our time, he had essentially no visual information about that region before seeing it himself. The still photos and filmed documentaries I have seen of the northern Polar region show a place of stark beauty. I have visited many mountaintops in New Mexico, Colorado and California that gave me a feel for the tundra. But no film or book can capture the crystalline air, the mystery of glacier-sky horizon lines, or the summer sun skirting the edge of the earth without setting. Nothing can prepare you for ice mountains thousands of feet deep nor the sight of huge Arctic wolf paw prints nor the airplane-loud roar of multiple cliff waterfalls.

It is now almost four years ago since I made my one visit to the High Arctic of Baffin Island, closer to the North Pole than the southern edge of the Arctic Circle. With that trip I came to understand Seton’s rhapsodic descriptions. For a very long time I have wanted to find a way to Aylmer Lake – increasingly so since seeing Baffin.

On to Aylmer Lake

Travel in the Arctic is dauntingly expensive, but I very much want to find a way to finance a trip to Aylmer Lake. Perhaps Crowd-source funding? Winning a lottery? I’m open to whatever ideas anyone may have.

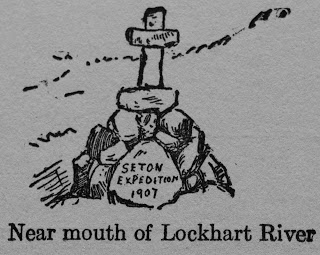

Seton built rock cairns to mark his expedition route. Two are of particular interest to me. One marks the Sandhill Bay campsite; the other, the place where the Lockhart River enters the lake. Could those cairns still be there over a century later? I would like to search for them – they may still exist. I looked for a particular cairn on Baffin and found it unchanged from its building over forty years earlier.

The account of Seton’s Arctic trip served as an inspiration when I was in my early twenties and may in some way have led me to Baffin, even though it was decades later. In honor of the Chief, I will provide a short account of my Arctic trip in the next two essays. I would like to have shared the Baffin experience with him. He would have been mighty pleased with what he would have seen there.

Featured image: Drawing of Lockhart River cairn (1907) by Ernest Thompson Seton