(Seton unfortunately never explored Baffin Island, but reading The Arctic Prairies inspired my interest in the far north, so in lieu of a Seton account, I offer my own.)

ONE of the goals of Seton’s 1907 Arctic trip was to find and study Musk-ox (Ovibos moschatus), the only survivor of the ice age mega fauna. He went looking for them north of Aylmer Lake. Glorious and huge, they are, all them together, of insignificance compared to the true lord of the north – as duly noted by Seton:

But a new force is born on the scene; it attacks not this hill or rock, or that loose stone, but on every point of every stone and rock in the vast domain, it appears – the lowest form of lichen…soon another kind follows…then another…which in due time prepares the way for mosses higher still. In the less exposed places these come forth, seeking the shade, searching for moisture, they form like small sponges on a coral reef; but growing, spread and change to meet the challenging contours of the land they win, and with every victory or upward move, adopt some new refined intensive tint that is the outward and visible sign of their diverse inner excellences and their triumph.

He wrote a lot more about these most diminutive beings and made many illustrations of the lichens and mosses found along the way. Sadly, there are no Musk-ox on Baffin Island. It does not, however, lack for lichens. Just as Seton described for the western regions of the Arctic, lichens seem to have made a home on just about every rock we saw; central Baffin is a world of loose rock from pebbles to basketball and desk-sized rock, and often larger. Many of the millions of rocks host from one to many lichens, presumably numbering into the billions of individuals of numerous species. (There were plenty of mosses as well.)

Patrick Webber, botanist

Dr. Patrick Webber, whose 1960s research inspired our 2009 expedition (see previous essay) gave me assignments covered in two pages of hand written notes (I still have them). Separately, and most importantly, he gave me a large packet of information on lichens. He wanted me to measure one. I’ll restate this: from among an infinity of lichens on Baffin, he wanted me to search out one particular individual measured in 1963 and again in 1967. I was to check on its progress and I suppose, give it his regards. I thought that finding planets in distant solar systems would likely be more easily accomplished. Worse yet, this individual was of the species Alectoria minuscula, which as far I could tell was the single most common organism in that region.

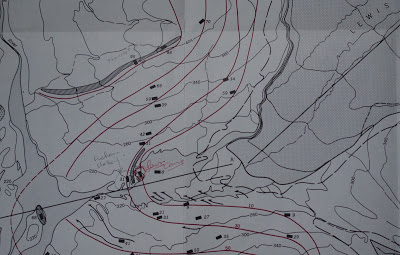

Fortunately, the search area narrowed down considerably. To the east, the torrent of water known as the Lewis River arises from its namesake glacier, itself an arm of the Barnes Ice Cap. On its way to the mighty Isortoq River, the Lewis reaches a confluence with another fast stream, the Striding River, so-named by Dr. Webber long ago when it was possible to walk across. (Like the Lewis, it is now an impressive flood during the summer.) He gave me a map showing that the lichen – #5 by name – lived near the corner where the two rivers came together.

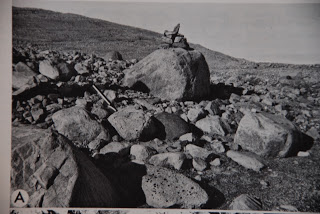

A tall rock cairn had been built beside #5 back in 1963. Given the ferocity of polar winters and the possibility of massive floods, we were not certain that the stone monument would have survived the decades. Expedition leader Dr. Craig Tweedie and I dutifully marched off into the endless felsenmeer of naturally occurring cairns. Perhaps because he is taller, Dr. Tweedie spotted Dr. Webber’s cairn before I did. Remarkably, it had changed not at all in forty-six years. We knew this because we had a photograph.

Lichen #5

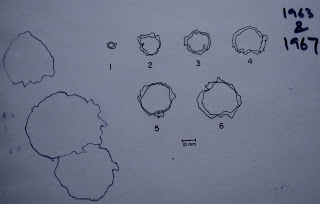

Lichen #5 was known to have lived on an average sized rock, about the scale of a 35 gallon Rubbermaid “ActionPacker” storage box of the kind in which we had transported our expedition gear (we had several of these). Fortunately, we also had a photograph of the rock which was right where a retreating glacier had left it long ago. (See #5 at roughly the center of the sketch.)

I had one more piece of information, a sketch Dr. Webber had made of #5 and its companions nearly a half century earlier. In 1963, #5 had been about 2cm across; four years later it had shown modest growth as shown by the overlapped sketches from the two years.

Then – there it was! I re-photographed the scene as closely as I could to match the 1963 photographs.

I then re-measured #5 to find that while its circumference had expanded – as expected – the center part that had existed in 1963 had died out. At its greatest extent, #5 now measured 6cm. (See sketch, left side, #5 with arrow and 2009 date.)

I took many photos (#5 is to the left of the yellow ruler). Soon thereafter, we made a satellite phone call to Taos to let Dr. Webber know of our re-discovery. On a trip that can only be described as thrilling, one of the highlights was finding diminutive #5 still active on its rock, expanding like an exploding star.

Lichenometry

Our small friend has taken its part in “lichenometry,” the measurement of lichen growth rate. Lichens appear to grow at a relatively predictable rate. This is useful for dating everything from medieval buildings to the rate of glacial retreat. Lichens don’t grow under the ice, but do colonize rock soon after the glacier has melted away. The question is, how long has a particular spot been ice free? By measuring the size of lichens, it is possible to establish a probable date for when the rock was no longer beneath glacial ice. I made a new series of measurements all the way to the current end of the life zone near the edge of the retreating glacier. Someday maybe other researchers will hike up the Lewis valley to find out how my own little crop of Alectoria’s are faring.

David L. Witt on Baffin Island tundra, Barnes Ice Cap behind, and sky above the ice