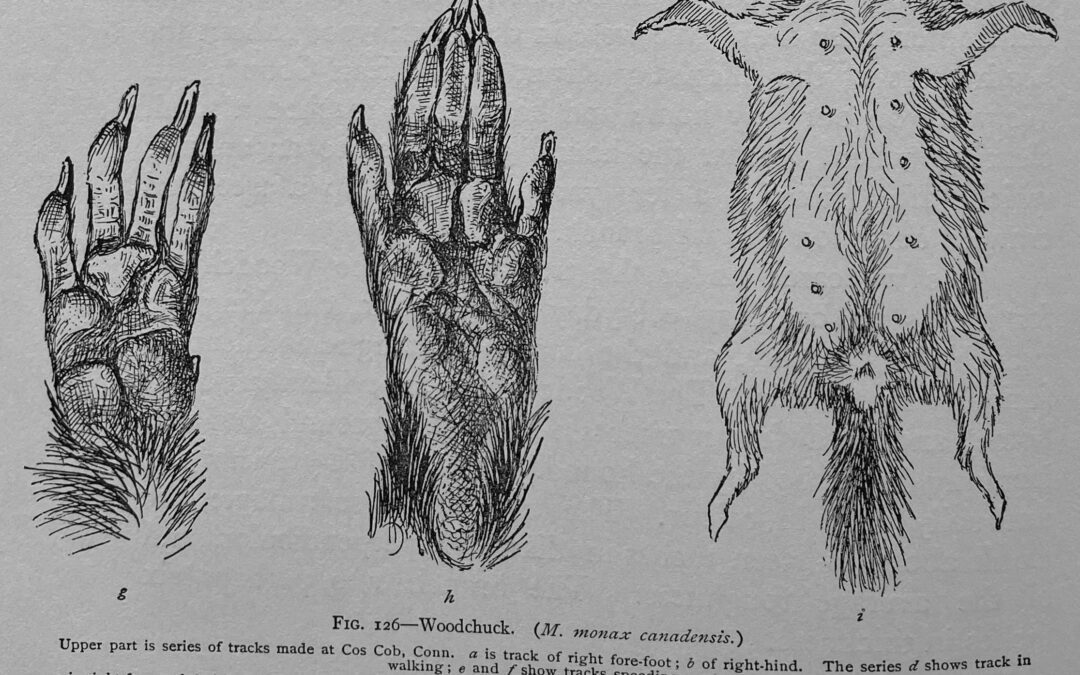

Woodchuck details, Ernest Thompson Seton

(This is an excerpt from Life-Histories of Northern Animals by Ernest Thompson Seton. Published in October 1909, Seton chronicled the lives of 60 species in a massive two-volume work including ecological and behavioral information and innovations such as range maps. Given the limitations of the blog format, I am presenting only a small part of what he wrote about each animal. I have applied very light editing in a few instances.)

Marmota monax (Erxleben). French Canadian: le Siffleur. Cree: Wee-nusk’. Ojib. Saut. & Musk.: Ab-kuk’-wah-djees. Chipewyan: Thel’-lee-cho. Yankton Sioux: Hob-cush-a.

Environment

(Pg. 420) This is a forest animal, but prefers the edges of sunny openings rather than the gloomy depths, and at all times in found in high, dry situations. Wooded clay banks and gravelly ridges are much to its taste, and its distribution…The existence of a Woodchuck depends on its den or burrow. This is either in the woods or on the rolling pastures, but by preference on the border land between.

Sanitation

(Pg. 424) As soon as the animal develops an elaborate home it must develop sanitation or suffer from disease.

Some creatures that fear neither weather no foes, go forth into the air to drop their dung. There are many times when the Woodchuck cannot well do this, and to meet the difficulty it has invented a dry earth closet. [Dr. C. Hart] Merriam points out that the main gallery of the Woodchuck’s burrow commonly terminates in a little pocket, where its excrement is found buried.

From time to time this is removed, and “mounds in front of the large holes frequently, if not generally, contain accumulations of the animal’s excrement, and in one case I removed fully half a bushel from a single mound.”

These midden-heaps of the Woodchuck are likely to furnish much light on the history of the individual, just as the midden-heaps of the Paleoliths are our principal histories of their makers. Every scrap of bone or undigested food will tell a little story to those who can read such things.

The Long Goodnight

(pg. 427) Throughout the autumn, old and young are busied storing up food, not in warehouses or vaults that robbers might rifle, but in their own skins, as fat, that will keep them doubly warm until absorbed. Their winter nests also are warmly lined and placed far beyond the reach of frost.

About the last of September they retire for the season, and all investigations hitherto have proved that sleeping in each winter den there is either a solitary young one or a very old one, or else a pair—possibly the pair of last season, reunited as soon as it was the pleasure of the lady to reunite.

The Woodchuck Sees Its Shadow (or not)

(Pg. 429) The Woodchuck sleeps in complete torpor for weeks. But a popular superstition has it that each year, on the second day of February, he comes out into the day. If he then sees his shadow on the snow he retires for another six weeks’ slumber. If, on the other hand, no shadow is visible, he continues more or less active into the spring.

This superstition seemingly originated among Negroes of the Eastern Middle States, and has this much of truth for foundation: The Woodchuck sometimes comes out as early as the first week of February. If at that time the sun shines brightly on the snow, it means frosty weather, and probably a late spring. On the other hand, no snow and low hanging rainclouds, are evidence of an open winter, and that fosters an early activity on the part of the Woodchuck.

DLW note:

Some years later, In Lives of Game Animals, Seton recorded that the Yellowbelly Marmot of the Rocky Mountains (Marmota flaviventris) purrs like a cat. I can confirm from personal experience that this is true.