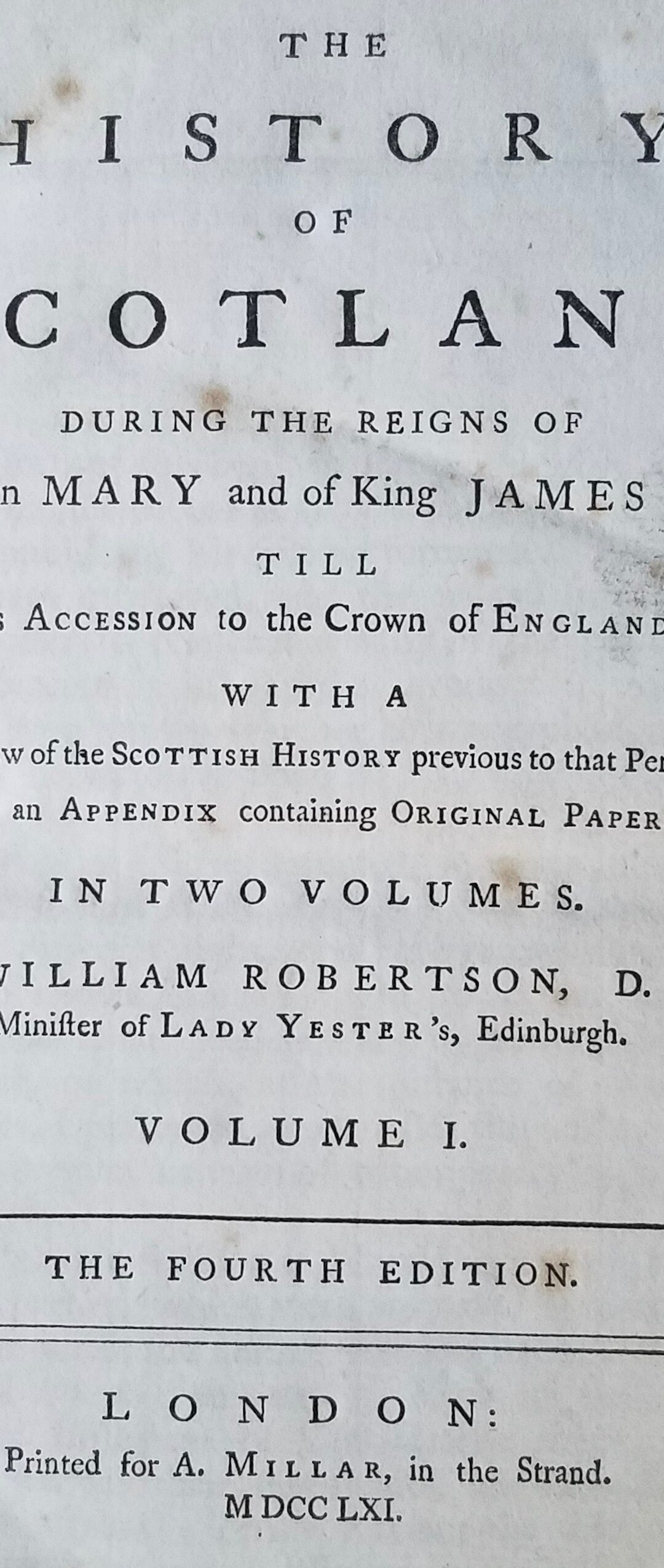

Title Page, The History of Scotland

George, Fifth Lord Seton played a pivotal role in the Battle of Langside on May 13, 1568, determining the future of Scotland. One account comes from William Robertson’s The History of Scotland published in 1761. I have modernized his spelling. I also learned a great deal from the Mary Queen of Scots website written by Robert Stedall.

With the help of Seton, Sir James Hamilton and others, Mary Queen of Scots escaped imprisonment on May 2. An army of supporters immediately gathered around her. They closed in on Glasgow but were met with an opposing army of her half-brother James, the Earl of Moray, Regent of Scotland. The armies met outside the small town of Langside.

Queen Mary’s Army

William Robertson: “On the first news of Mary’s escape, her friends, whom, in their present disposition, a much smaller accident would have roused, ran to arms. In a few days, her court was filled with a great and splendid train of nobles, accompanied by such numbers of followers, as formed an army above 6000 strong. In their presence, she declared that the [her] resignation of the Crown, and other deeds she had signed during her imprisonment, were extorted from her by fear” and thus were void. (Pg. 453-454)

Moray was in a difficult spot. Outnumbered by Mary’s ardent supporters, the risk of battle seemed too high, but with each day’s delay, her strength in numbers would only increase. Robertson: “In war, success depends upon reputation as much as upon numbers; reputation is gained, or lost, by the first step one takes; in his circumstances, a retreat would be attended with all the ignominy of flight, and would at once dispirit his friends, and inspire his enemies with boldness.” (Pg. 455)

No choice but to fight.

Too Soon Too Little

Not just Moray, but Mary as well would have been better served by gathering more forces over a few more days. But the ambitions of the Hamilton family—seeking glory and an unencumbered path to control of the throne of Scotland—needed an immediately victory. George Seton’s advice to Mary in all this is unknown.

May 13: “Mary’s imprudence, in resolving to fight, was not greater than the ill conduct of her generals in the battle. Between the two armies, and on the road towards Dunbarton [a castle], there was an eminence called Langside-Hill. This the Regent had the precaution to seize, and posted his troops in a small village, and among some gardens and enclosures adjacent. In this advantageous situation he waited the approach of the enemy, whose superiority of cavalry could be of no benefit to them on such broken ground.” (Pg. 457)

The Scottish horse was led by George Seton.

Don’t Just Bring A Claymore Sword To A Gunfight

Moray found support from an experienced office corps, especially William Kirkcaldy, the finest military mind in Scotland at the time. While Moray and others took charge of the main contingent, Kirkcaldy headed up a small group of what might be called special forces today. They secured a ridge above Langside. Armed with “hagbutters,” a primitive matchlock firearm, and sheltered by walls, they tore apart the cavalry charge led by Seton and Sir John Herries riding in support of 2000 infantry.

Mary’s lead general, Archibald Campbell, Fifth Earl of Argyll, attempted counter-moves but was checkmated by the ever-resourceful Kirkcaldy. Accounts differ, but Argyll for whatever reason was taken out of the battle, depriving the army of his essential leadership. Mary either did or did not seek to rally her troops. In forty-five minutes Mary’s forces lost only a hundred of their number (or fewer) before fleeing the battlefield. Moray’s reportedly lost only one killed.

Their hearts may not have been in it. Scots killing Scots, although not all that rare, seems not to have been the feeling of the moment. Robertson: “Few victories, in a civil war, and among a barbarous people, have been pursued with less violence, or attended with less bloodshed. Three hundred fell in the field; in the fight scarce any were killed. The Regent and his principal officers rode about, beseeching the soldiers to spare their countrymen. The number of prisoners was great, and among them many persons of distinction.” (Pg. 457-458)

One of them was George Seton. After four centuries of Seton-Winton warriors starting from the twelfth century, this seemed to be the end. As he languished in prison awaiting certain execution, Seton couldn’t have imagined that his family’s final defeat would have to wait another 177 years and eleven months.

I think it likely that Ernest Thompson Seton must have been more than a little in awe of his remarkable ancestors. Like them, he too proved to be a fighter to his last breath.