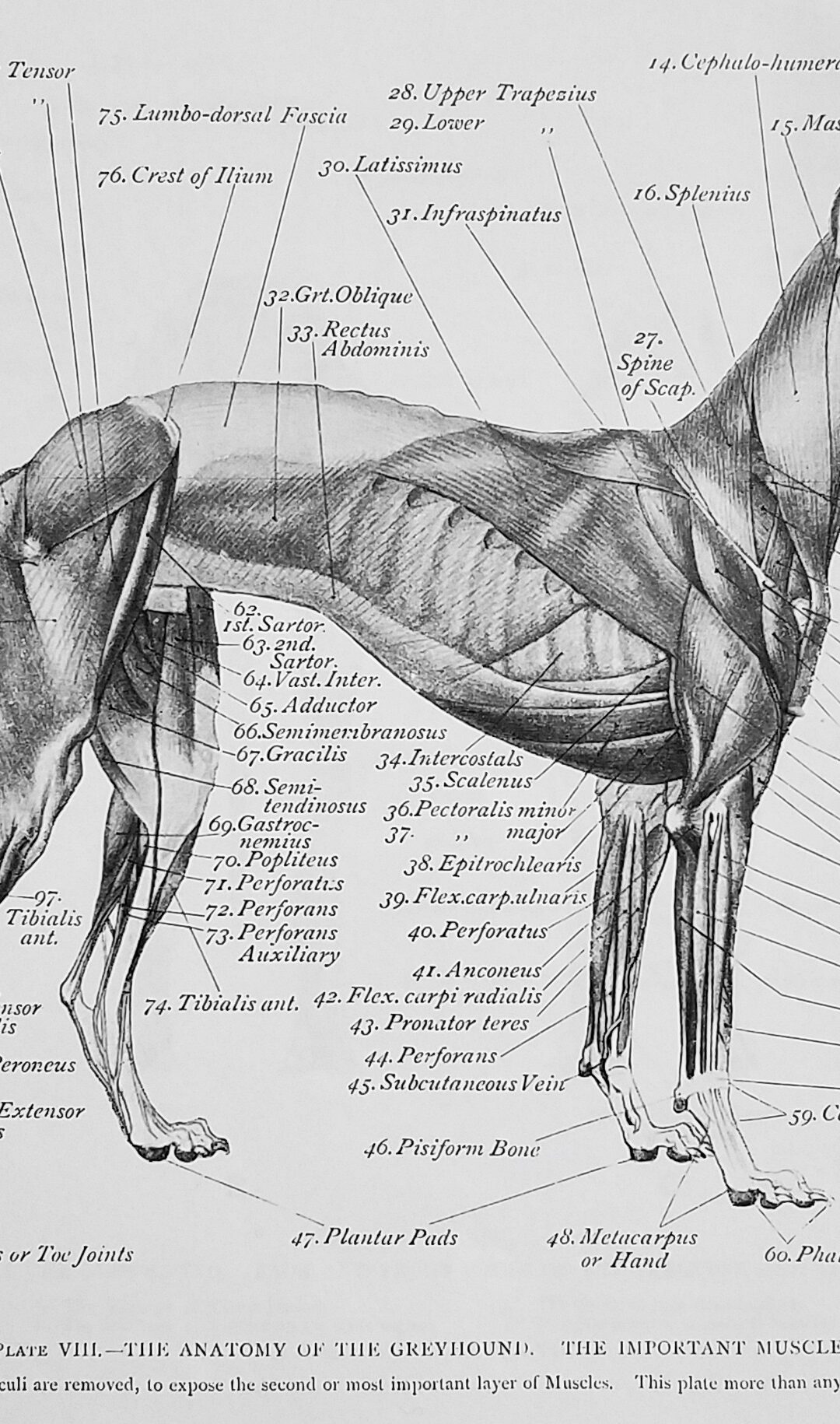

The Anatomy of the Greyhound. The Important Muscles (reproduced from the book).

Seton published a major work in 1896, Studies in the Art Anatomy of Animals. It is an exquisite blending of art and science.

The two years of Seton’s life following his return east from New Mexico in early 1894 set his course for the next several decades. Reacting in part to the tragic death of Lobo (see “Lobo, Wolves and Wildlife Conservation” section) Seton resumed his career in illustrative art with renewed energy.

His mastery in art came in the form of high-level illustration. While he failed to exhibit his major painting La Pursuit in the 1895 Salon, sketch studies of wolves were accepted. Seton’s facility at showing action, movement, and personality of animals was perhaps unmatched by anyone else at the time. This more than made up for the lack of interest in his out-of-contemporary-fashion oil paintings. Drawing proved a better match to his personality. Ever restless, impatient and endlessly innovative in terms of ideas of what to do next, the significant time commitment required for oil painting was likely more painful than pleasurable. He simply had too much to do and say to be held back working for hours in a studio on a single project.

The Animalier Makes Unsurpassed Drawings

The one hundred drawings in Art Anatomy represent an exquisite blending of art and science based on meticulous specimen study with reference to earlier classic works. He also went all out in coming up with a descriptive subtitle: “Being a brief analysis of the visible forms of the more familiar mammals and birds. Designed for the use of sculptors, painters, illustrators, naturalists, and taxidermists.”

Seton’s finest animal portraits demonstrate an intrinsic knowledge of interior structure that makes our exterior experience of the fur or feathers all the richer even if we can’t see what lies beneath. Seton believed anatomical knowledge was even more important for animal depiction than for the human figure:

“The argument for the Art Anatomy of Animals is yet stronger – the knowledge of it is absolutely indispensable. The figure-painter always can pose his models, and paint what he sees. The animalier must continually work from knowledge of the form, his models never pose, and, unlike those of the figure-painter, they are invariably au naturel.”

A Multi-Year Process

The bulk of Seton’s direct work on this project seems to have taken place from 1894 to 1896, primarily or entirely in France. He had, however, long prepared for the task over years of taxidermy study. He was at this time in his mid-thirties and in the final throes of his imagined easel painting career.

Since this was his first major work and he was still little known, Seton listed his qualifications on the title page: Two monographs (on mammals and birds of Manitoba), the Lobo story, his acceptance by the Salon, and his official title as “Naturalist to the Government of Manitoba.” (Published under the last name of Thompson rather than Seton.) Seton seems not to have recorded the story of how he sold this work to the publisher, Macmillan (London) nor do we know how much they may have paid him.

Little About Grace

There is one more account which does not survive in much detail. The period of Seton’s work on Art Anatomy coincided with his courtship of Grace Gallatin whom he met on the S.S. Spaarndam in July 1894 during that ship’s journey from the U.S. to Europe. His marriage to Grace took place around the same time as the publication of the book, in the spring of 1896. Seton acknowledges his soon-to-be wife in the Preface. But in his autobiography Seton fails to adequately credit Grace’s vital contributions to his career. Indeed, in all his writing through the following five decades, he scarcely mentions her at all.

Art Anatomy set a high standard for Seton’s subsequent non-fiction work in a multitude of studies from Indian sign language to the magnum opus of Lives of Game Animals. (See the “Annotated Publications” section for the complete list.)