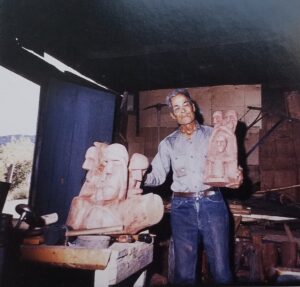

Patrociño Barela photo by Robert Beadles. Seton photo by unknown photographer.

During my career, I have written biographies of two artists: Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946) and Patrociño Barela (ca. 1900-1964). They likely never met (or at least no supporting record has been found). Although they passed in different years, Seton died during the morning of October 23; Barela died in the pre-dawn hours of October 24.

They share a closeness not only defined by the calendar, but also in terms of their role as outsiders: Seton as painter was never accepted as a fine artist, although in his understanding of wildlife subjects he had no equal. Barela, perhaps the most original and emotionally honest artist ever to work in New Mexico, was mostly ignored outside of a small group of supporters in Taos.

The Artist as Subversive

Both were iconoclasts in their own way. While Seton desperately wanted acceptance by the art and literary establishment, he also remained a dedicated subversive, caring little for social behavioral norms while also promoting radical ideas such as the sentience of animals and just treatment and respect for Native Americans. Barela was radical as an artist, bearing his soul with a daring seldom matched by anyone else and in so doing, exposing deep existential truths about the human condition.

Both were deeply spiritual and believers in Jesus Christ as the greatest of teachers. But neither cared about religion because of the load of dogma and rules and deference to authority required of the true believer.

Meaning of Barela Artwork

Although others made note of Barela’s words, he left none of his own behind. Instead we have a huge output of known artwork (wood sculptures) that my co-author Edward Gonzales and I spent years studying and interpreting. We wrote of him: “In his carving, Barela explored the human condition by releasing, with great wisdom, the individual figures engaged in the struggles of personal and spiritual growth he saw contained within each chunk of wood.”

Meaning of Seton’s Work

Seton’s artwork contained little that could be described as mystical, instead striving to convey a sense of the subject as individual or as entity in relation to the larger environment. Seton wrote sparingly about spirituality, but made clear its absolute centrality to his life. In his “Buffalo Wind” essay, he used the metaphor of the river. I wrote about this in my book on Seton: “The river seeking the sea is like the individual soul merging with the larger cosmos at death. (He) does not accept anyone else’s religious revelation as valid for him, and neither does he invite us along with him—this revelation is purely personal. He does, however, have a purpose in the sharing: he suggests that the way exists for us if we have the fortitude to seek it.” I find the same message in Barela’s wood carvings.

Barela died alone in a studio fire in the middle of the night amidst wood shavings, unfinished and completed carvings. He is buried close to where I live and I sometimes visit his grave. Seton died in the bedroom of his “Castle” with his wife Julia either at his side or nearby. Fourteen years after his death, his cremated remains were scattered from an airplane flying above the Castle. I regularly visit the Castle, sometimes staying there overnight in a room adjacent to where Seton spent his last hours.

Omaha Prayer

The Woodcrafters (starting with Seton) recited a simple prayer at the end of their gatherings, borrowed (or appropriated) from the Omaha Tribe. I hope they asked for permission to use the prayer since it is one meant to convey the humility of the individual (and all individuals) within the larger universe. (Hear Robbie Basho version) I believe that Barela have agreed with the sentiment:

“Father, a needy one stands before thee;

I that sing am he.”