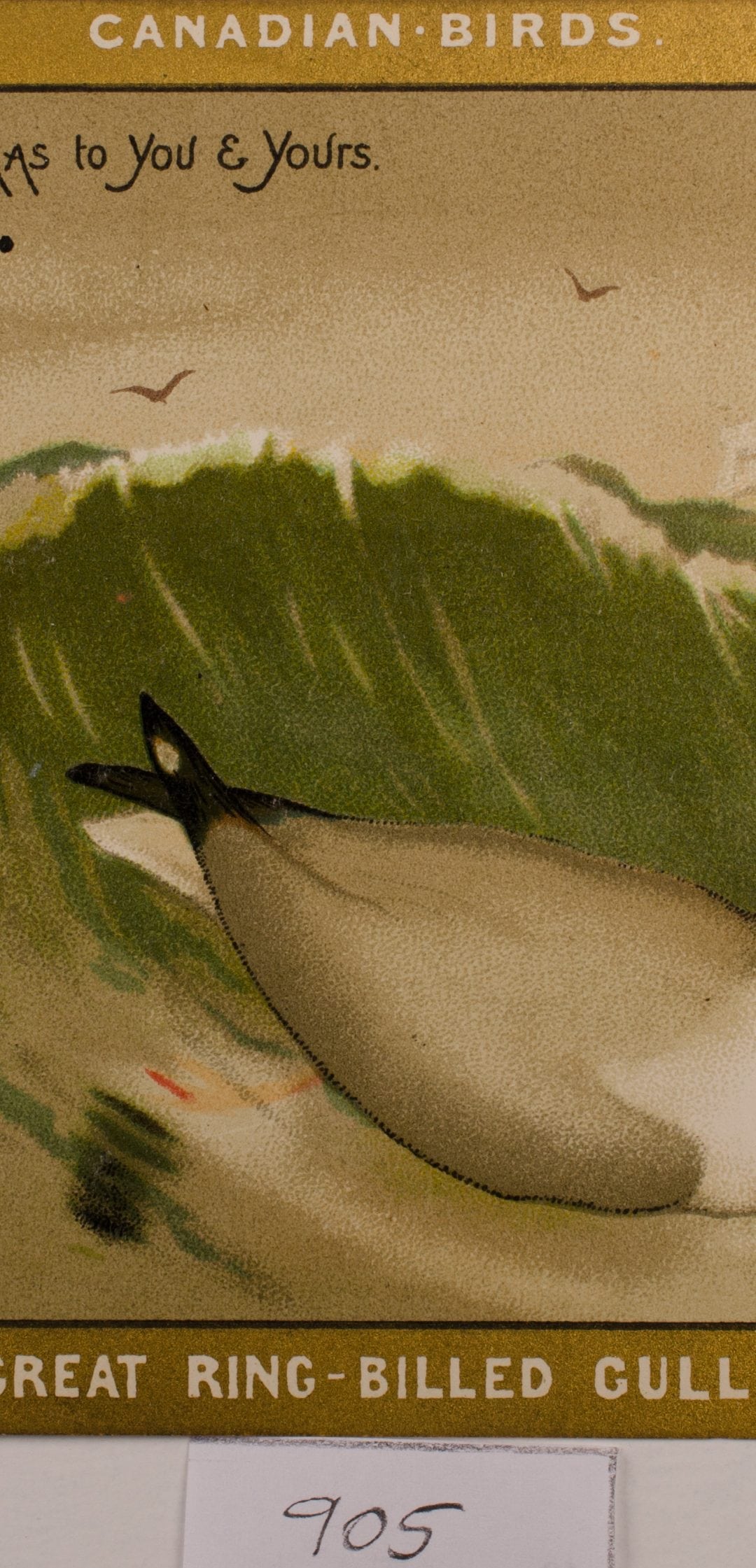

Great Ring-Billed Gull, Academy for the Love of Learning

Upon his return from London (and abandonment of life as an art student), Seton moved back in with his parents for what must have seemed an interminable five months. Apparently the only thing he and his father Joseph agreed upon was how much they detested one another. (Seton claimed that Joseph presented him with a bill for the cost of his upbringing.)

Joseph, a bit of a schemer, and an unsuccessful one at that, developed a plan to take advantage of homesteading rules in Manitoba. As in the U.S., pioneer types could stake out a bit of land, make improvements and after three years, and then own that section. Joseph determined to send five of his sons to each take on adjacent pieces of property, after which their dad would show up to run the new family farm empire.

Seton had not the slightest interest in helping Joseph fulfill his dreams, but given the chance to go west, boarded a train for Manitoba with a bit of cash left over from his first commercial art assignment (see featured example above), plus a few chickens (which were in great demand in Carberry, Manitoba and thus a valuable commodity). For the next year and a half Seton tried his hand at homesteading, but was happiest when out exploring the wilderness. But by November 1883, he had to admit to his practical side, returning east, not to Toronto, but to the center of the North American art world, New York.

The Winnipeg Wolf

There were many adventures along the way including making the acquaintance of First Nations people, undergoing a successful operation for a hernia, and enduring the loss (by drowning) of his closest friend. I must give greater attention to his most “thrillsome” experience. Writing about the experience almost sixty years later in his autobiography, Seton told of his encounter with a great wolf, as seen from a train:

“As we neared St. Boniface, the eastern outskirts of Winnipeg, we dashed across a little glade thirty yards wide, and there in the middle was a group that stirred me to the very soul. In plain view was a great rabble of dogs…And in the midst, the center and cause of it all, was a great, grim, grisly wolf…There he stood, with his back protected by a low bush, all alone—resolute—calm—with bristling mane, and legs braced firmly…ready for attack in any direction…I longed to go and help him. But the snow-deep glade flashed by, the poplar trunks shut out the view, and we went on to our journey’s end.”

This wolf was featured in Animal Heroes (1905), a collection of short stories in his series of popular books introducing readers to the wonders of the animal world. Not unlike the urban dwelling coyotes of today, the Winnipeg Wolf chose to live near the world of humans and their dogs—facing that world of enemies alone—a choice ultimately leading to his death. Seton wrote the story when he too was surrounded with adversaries who unfairly accused him of nature-faking—assigning intelligence and morality to animals—and who tried to close in on him damaging his career. More than once in his life Seton felt that his enemies threatened to tear him apart and that he often stood alone against them. Seton also lived part of the time in the wild, but was also irresistibly attracted to cities.

In 1901, at the beginning of The Trail of the Sandhill Stag, he referred to his time in 1880s Manitoba: “To the Reader: These are the best days of my life. These are my golden days.”