Seton’s early science writings are less known than his wildlife stories but demonstrated important insights.

Roger Tory Peterson

Writing in 1941 in the Preface of A Field Guide to the Western Birds, Roger Tory Peterson gave credit to Seton’s influential work:

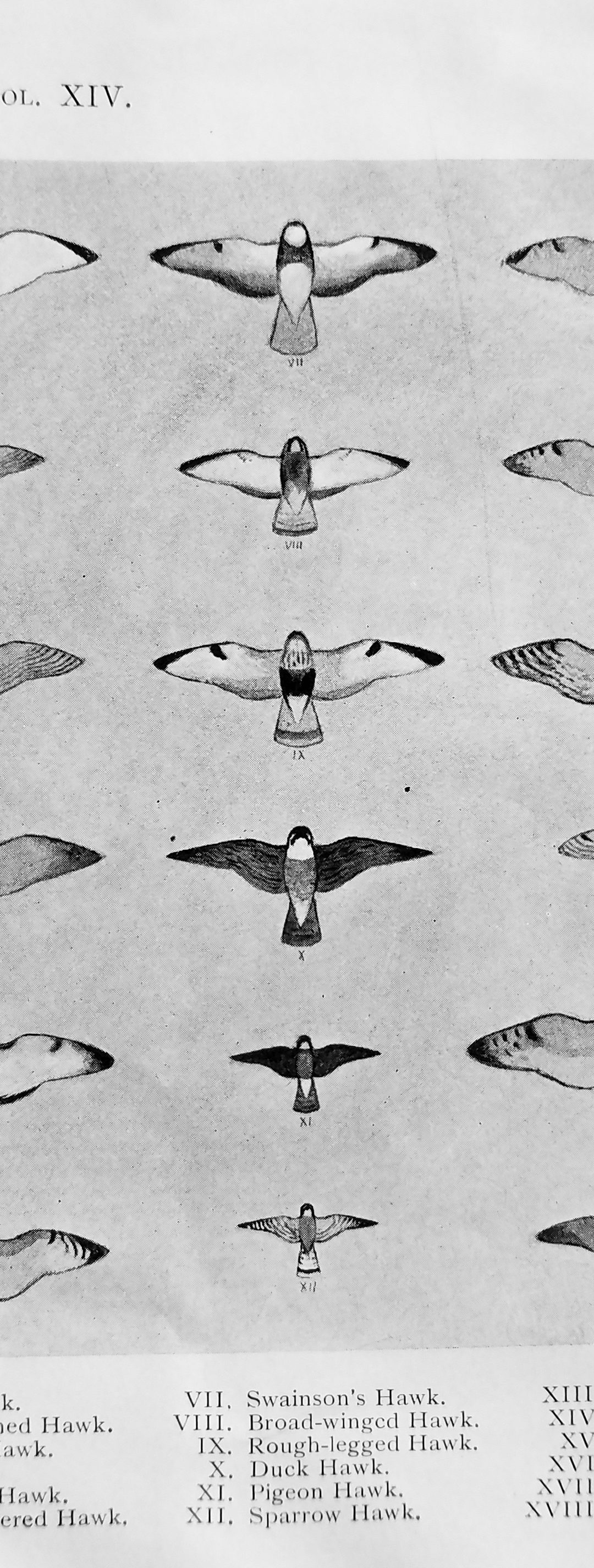

“It was that pioneer, Ernest Thompson Seton, who first tried the idea of pattern diagrams as a method of teaching bird identification. He published diagrammatic plates in The Auk, showing how Hawks and Owls look in flight overhead.”

Peterson noted that before Seton bird identification had concentrated on what birds look like up close (still the prevailing methodology today). Yet, frequently we see birds not close up but far away. Seton (writing as Yan in Two Little Savages), thinking about identification of ducks, determined that he could, according to Peterson, “put their labels or ‘uniforms’ down on paper [so] he would know these same Ducks at a distance.”

He continued, “It was on this idea that my Field Guide to the Birds…was based.”

Seton published the following article in The Auk, Vol. XIV, No. 4, October 1897 under the name the then used, Ernest Seton Thompson.

Directive Coloration

“The Protective Coloration of Birds has been much studied of late, but I do not know of any paper treating of their Directive Coloration.

While living on the Plains [of Canada] in the [eighteen] eighties, I made many studies or as I then called them ‘flying descriptions” of birds, and on putting these together recently in a methodic scheme I arrived at a few general principles that may prove of interest.

I can best illustrate by taking an example from mammals. The common jack rabbit when squatting under a sage-brush is simply a sage-gray lump without distinctive color or form. Its color in particular is wholly protective, and it is usually accident rather than sharpness of vision which betrays the creature as it squats. But the moment it springs, it is wholly changed. It is difficult to realize that this is the same animal. It bounds away with erect ears, showing the black and white markings on their back and under side. The black nape is exposed, the tail is carried straight down, exposing its black upper part surrounded by a region of snowy white; its legs and belly show clear white, and everything that sees it is plainly notified that this is a jack rabbit. The coyote, the fox, the wolf, the badger, etc., realize that it is useless to follow; the cottontail, the jumping rat, the fawn, the prairie dog, etc., that it is needless to flee; the young jack rabbit, that this is its near relative, and the next jack rabbit that this may be its mate. And thus, though incidentally useful to other species at times, the sum total of all this clear labeling is vastly serviceable to the jack rabbit and saves it much pains to escape from real or imaginary dangers.

As soon as it squats again all the directive marks disappear and the protective gray alone is seen.

Protectively Colored, Directively Colored

In the bird world the same general rule applies. When sitting, birds are protectively colored; when flying, directively.

The general rule may be topographically rendered: Color of the upper parts, Protective; color of the lower parts, Directive. In the drawings, I have shown only certain birds of prey. All of these present a distinctive pattern when viewed from below as they fly. It is inconceivable that this pattern should have a protective object, so if it have [sic] a purpose at all it must be a directive one.

An evidence of this is seen in the tact that all birds with ample wings and habits of displaying them bear on them distinctive markings—e.g., Hawks, Owls, Plovers, Gulls, etc. Every field man will recall the pretty way in which most of the Plovers identify themselves. As soon as they alight, they stand for a moment with both wings raised straight up to display the beautiful axillar pattern; a pattern distinctively different in each kind. And no doubt their end is served by telling friend or foe alike that this is such and such a species.

On the other hand, birds whose wings in flight move too rapidly for observation are without markings on the underside.

Directive Marks

Though it is proverbially dangerous to classify animals with a view to one set of characters only, it is nevertheless interesting and often instructive. Among the Hawks the presence of the wrist spot characterizes the Buteo group including the Eagles and the Osprey.

The Falcons on the other hand, in common with the Acciptres and Circus, are without the wrist spots and have nebular banded primaries.

Exceptions to the rule that directive marks belong to the lower surface are seen in the Redtail, whose rufous tail is its most distinctive mark; in the white rump-spot of the Marsh Hawk and the head-markings of the Goshawk, Peregrines and Sparrow Hawks.

Among the Owls the wrist spot seems to characterize those that have ‘ear tufts.’

In this brief paper and single plate I have limited myself to our northern birds of prey but enough material has been gathered to justify a much more extended application of the generalizations indicated.”