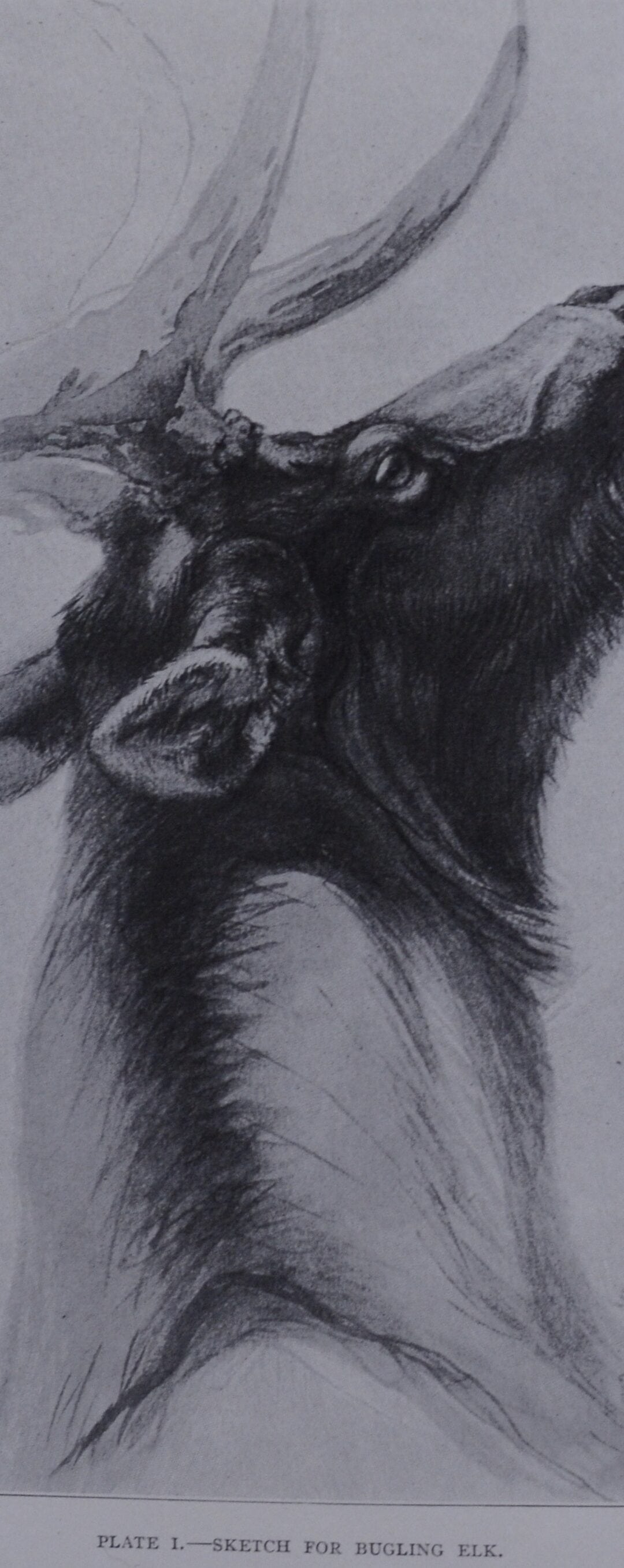

Sketch for Bugling Elk by Ernest Thompson Seton

(This is an excerpt from Life-Histories of Northern Animals by Ernest Thompson Seton. Published in 1910, Seton chronicled the lives of 60 species in a massive two-volume work including ecological and behavioral information and innovations such as range maps. Given the limitations of the blog format, I am presenting only a small part of what he wrote about each animal. I have applied very light editing in a few instances.)

“The Wapiti, Canada Stag, American Red-deer or Round-horned Elk. French Canadian: le Cerf (male); la Biche (female). Cree: Mus-Koose. Ojib. and Saut.: Mush-koose. Yankton Sioux: Eh-kag-tchick-kah. Ogallala Sioux: Hay-hah-kah (male).” Cervus canadensis Erxleben.

(pg. 45) In early days the total range of this species was about 2,500,000 square miles, over half of which it was, by all accounts, very abundant. We are safe, therefore, in believing that in those days there may have been 10,000,000 head.

(pg. 45) The beginning of the nineteenth century saw the Wapiti perfectly described, catalogued, and started on the road to extermination. Thenceforth, travelers in Eastern America were obliged to record only the reminiscences of old settlers or the discovery of fossil horns and skulls. A melancholy shrinkage is set forth, a shrinkage which went on with tremendous and increasing rapidity until near the end of the century.

Elk Conservation

(pg. 46) The dwindling process went on everywhere till about 1895. That was the low-ebb year in many parts of America for many kinds of game, but it was also the year awakening. The lesson of the vanished Buffalo had sunk deep in men’s minds. Thinking people everywhere recognized that unless the methods then practiced were stopped all our fine game animals would go the way of the Buffalo. They saw, too, that there was nothing to gain by extermination, and much to lose. Game protective societies, founded in various parts of America by men who viewed with hate the approaching desolation of the wilds, have now secured sound legislation for the protection of harmless wild animals, and public sentiment has secured a rigorous enforcement of these new laws. Thus, in many regions the process of extermination has been stopped.

In all regions where adequate protection has been accorded the number has increased; and there can be no doubt that, with a system of permanent safe havens, proper limitation of bags, and an absolute prohibition of repeating rifles and of the sale of game, we may keep these fine animals with us as long as we have wild land for them to range on — that is, forever.

Tracking the Elk

(pg. 49) (Here we follow) the tracks of three Elk, travelling in the general direction of “down wind.” Here, crossing from the middle below out at the top left corner, is a stale track. Its size and general character, together with the place, show it to be that of a bull Elk. He was travelling (along) because, in spite of its dimness, we can see a faint sharpness at one side of the track and a suggestion of squareness at the other, showing the toe and heel marks, respectively, and also because on the bank, at the bottom, the tracks are shortened, showing that he was coming up.

In case of doubt, one can sometimes determine the direction of a doubtful track by lightly brushing away the snow. The wet ground below may have a clearer impression, or a ball of hard snow may remain to tell the tale. The track is stale; but how stale? Yesterday the wind came from the point he is headed for, and last night came the fresh snow; therefore he is twenty-four hours ahead, and though unalarmed — witness his easy stride and trailing toes — it might take several hours to come up with the maker of that track.

But the three we are following are quite fresh. (Note) is the track of a big bull, because the hoof – mark is 5 inches long (4 inches would be middle sized). His hoofs might be overgrown, but the tracks are wide apart, showing the thick body; and he has fine antlers, because the cow went through a four-foot opening, which he avoided for a wider door. Also, the snow is knocked off the lower branches where he passed, and a spike-horn rarely touches a branch with his antlers.

That he is not alarmed is shown by his short steps and the lazy dragging of his toes, as well as by his halting to drop, an important hunter’s sign. The track is fresh, because it was made since last night’s snow, but it is at least an hour old, because the sign at is no longer hot; is sprinkled, indeed, with hoar-frost.

Here, the bull “bedded.” He was there for an hour at least, because the snow under him is melted.

The (next) trail is that of a full – grown cow; a cow, because at the creature had stopped and straddled (told by the hoof marks) to leave the liquid sign; and full-grown, because the hoof-mark is 4 inches long.

Her trail shows no sign of alarm…she lay down, but rose up after she had been long enough to melt the snow perhaps an hour; looked about with the usual watchfulness of a cow, and lay down again in the same place for nearly as long, as shown by the second mark, not quite tallying with the first.

The (next) trail is that of a calf of the year, born late in May, and not yet (October) quite weaned. He lay down by his mother. But see, each bed is still wet with melted snow, and the tracks that were a couple of hours old are now quite fresh. We have jumped the three Elk.

Up spring the elk!

They sprang up when they heard us coming through the woods. See the long strides of the bull as he trotted off, no longer trailing his toes; see how all three fell into line! But what is this sign at J? That animal stayed to do something that all Deer do every few hours in cold weather, and nearly always on rising. She was not greatly alarmed (less so than the bull), or she would not have stayed, for the small quantity shows that she was not greatly pressed, therefore we may yet see them, for the Elk will swing round, probably to the left, as that is uphill, till they either see us or get our wind. Quick, a rapid advance – keeping a sharp lookout — here we are at the edge of an open glade, and there across it, gazing toward us, are the Elk. For a moment they stand, then up go their noses, and away they trot at speed, with the cow, as usual, in advance.